How to give bureaucracy back its brains

The ideas that revolutionized computing could do the same for government — but not in the way you think.

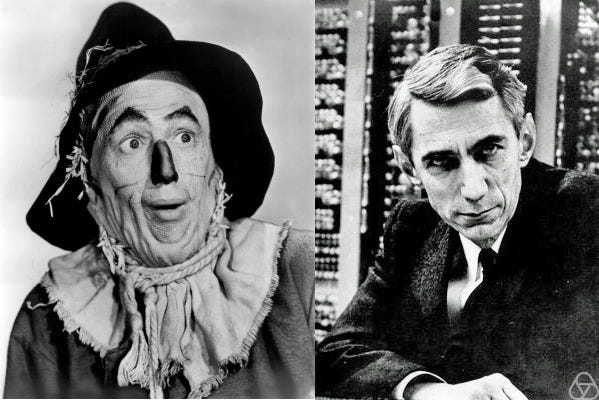

Claude Shannon is probably known to Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy as the legendary mathematician who laid the groundwork for modern computing by inventing a way to conceptualize information as “bits” — binary digits.

The tech titans are also likely aware that Shannon’s ideas spawned a new field of study, “cybernetics,” that reached well beyond computing, treating information as a unit of analysis as fundamental as matter and studying how it moves through systems ranging from thermostats to the human brain. They may realize that this broad framing made cybernetics appealing to a remarkably diverse range of figures, from American systems engineers to Soviet planners, from weapons designers to philosophers, and from 1960s countercultural champions to PC revolutionaries.

What they might not realize is how Claude Shannon could help them in the here and now, as they swagger into their campaign to reshape the federal bureaucracy through their self-styled “Department of Governmental Efficiency.” Instead of grandiosely promising to cut trillions or targeting individual public servants, the DOGE team could consider how lessons from the fundamental architecture of computing could help us fix government.

Cybernetics sounds like an oddball concept when you encounter it for the first time, as I did upon reading Dan Davies’ brilliant new book The Unaccountability Machine (already published in the UK, forthcoming stateside). The name “cybernetics” feels like something straight out of the 1950s, the range of eccentrics associated with the field inspires skepticism, and its basic concepts — that many systems rely on dynamics of feedback, for example — seem so obviously true as to be unremarkable.

But as with any great theory, the simple precepts of cybernetics become illuminating when they are skillfully attached to real-world scenarios. In the case of computing, that grafting was done with mathematics. Shannon developed equations that reduce information to bits and modeled a system’s capacity for processing them, thereby opening the door to the digital age. As Davies shows, the cybernetic thinker Stafford Beer reduced information to categories appropriate to different levels of an organization, and modeled how the whole enterprise can adapt to its environment — or not.

Management cybernetics was widely written off after it became associated with economic central planning — due in part to a bizarre episode in which Chile’s Salvador Allende recruited Stafford Beer to apply his methods before Pinochet’s 1973 coup and the era of the “Chicago boys.” But in the second decade of the “polycrisis,” in which one institution after another seems to be failing, the cybernetic approach is worth a second look. It’s a method completely consistent with market capitalism. And it gives us new tools to think about how institutions confront the complexity of the real world — theorizing information as something more than raw price signals, and management capacity as something more than brute market discipline.

The cybernetic spirit also aligns well with Niskanen Senior Fellow Jen Pahlka’s emphasis on letting bureaucracies focus on results rather than procedure, on end users rather than compliance czars. That’s one reason the political scientist Henry Farrell has grouped Davies and Pahlka together as leaders of the “adaptive” school of state capacity.

As Farrell explains:

Large-scale organizations (suffer from a) liability to produce outcomes that nobody plans and nobody actually wants, not because of malice, but because that is how big systems tend to work. They are specifically bad at dealing with complex environments, unless they can either attenuate that complexity, or model it internally, through better systems of feedback.

If we do not fix this growing problem, it’s hard to see how we will solve any of the pressing policy challenges that confront us. Farrell distinguishes the “adaptive” approach from a “big-fix” method that accepts the futility of most government interventions and focuses on just a few big bets to break out of our malaise. Operation Warp Speed is an impressive example of such a moonshot approach — but it’s hard to see how a government that combines political chaos with bureaucratic rigidity would execute other “big fixes” without the knife of an existential crisis at its neck.

It is also important to note that the diagnosis of institutional failure extends well beyond government. Plenty of private-sector actors have lost the trust of the public and seem to be flailing in a newly volatile, and politicized, world. Left-behind regions, inflation-pinched workers, and bailout-weary taxpayers might wonder whether the financial firms lubricating our economy are all that good at recognizing and responding to socially significant information.

It is tempting to cast bureaucracy as merely an “arm” of a government (or corporate management), controlled fully by elected officials (or board members) who act as the “brain” and are directly accountable to the citizenry (or shareholders). But that simple, anthropomorphized metaphor simply isn’t fit for purpose in a modern economy. Instead, we might turn to a military metaphor, in which elected officials are the generals and the bureaucracy forms the platoons. Those platoons understand the mission and the rules of engagement and are given the autonomy to execute within those parameters. To do that, bureaucracy cannot just be a limb. It needs a brain of its own.

And the brain, cybernetic thinkers will tell you, is merely an organ of information processing.

In this volume of Hypertext, Davies makes the case for cybernetics as a worthy supplement to the tools of economics and public choice by examining the case of public-sector outsourcing.

In response, Stanford political scientist Margaret Levi says Davies has uncovered a valuable new resource for thinking about public management. But she notes that our institutional crisis is not just about organizational maladaption to information flows. It’s also about powerful interests and how they respond to uncomfortable information.

We return to the outsourcing theme by sharing Pahlka’s eminently readable discussion of the problem in the American context, from her important new report, The how we need now.

Finally, Marc Dunkelman, author of Why Nothing Works, urges us to think not just about how too little information processing capacity can slow down projects, but also about the problems that come from having too many decision-makers and an unwillingness to make a decision in the first place.

As always, please share these essays widely, and if you’d like to write a response, send me your pitch — ddagan@niskanencenter.org.

David Dagan is director of editorial and academic affairs at the Niskanen Center.

Images: Shannon: Jacobs, Konrad, CC BY-SA 2.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons; Oz: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.