The rise of the caps and gowns

How education is transforming culture and culture is transforming politics

Over the past several decades, well within the firsthand memory of many living adults, the United States has experienced a series of overlapping social revolutions. Nearly every aspect of American life has been transformed: from the quality of citizens’ economic and educational opportunities to the ethos and leadership of major institutions, and from the demographic composition of the American public to the prevailing norms of culture, language, and behavior.

Government action was not the sole cause of these developments, and their consequences likewise extend far beyond the realm of politics. But ideological debate and partisan competition in America have come to separate those who have accepted or welcomed change from those who have found it costly or alienating. More than ever, the contemporary Democratic Party represents the groups who have willingly adapted to a complex world where the social value of education is rising, credentialed specialists hold increasing influence over policymaking, and the broader national culture has moved in a predominantly liberal direction.

The Republican Party, along with the conservative movement with which it is aligned, now serves as the voice of populist backlash to the authority of professional experts and cultural progressives, looking back nostalgically to a simpler era when a different cast of leaders held power and a different set of values and qualities were socially rewarded. As the journalist and political analyst Ronald Brownstein describes it, party conflict in America now sets a Democratic “coalition of transformation” against a Republican “coalition of restoration.”

Social, cultural, and technocratic change has mostly reinforced the existing partisan preferences of Black and white evangelical voters. But it has inspired many other Americans to rethink their political identities.

For decades, the most loyal members of each party’s popular base of support have been Black voters for the Democrats and white evangelical Christians for the Republicans. The rising political salience of social, cultural, and technocratic change has mostly worked to reinforce these groups’ existing partisan preferences. A white evangelical population that is habitually predisposed to favor traditional ideas, regard intellectuals with suspicion, and resist major shifts in social relations has naturally continued to identify with conservative Republicanism, even as the public appeals of Republican leaders have evolved over the course of the twenty-first century from emphasizing “family values” moralism to invoking ethnonationalist and populist themes. And most Black Americans – as well as other racial minorities, to a lesser degree – have remained faithful to the Democratic Party, as they stand to gain from the popular acceptance of egalitarian multiculturalism and have little reason to mourn the passing of “good old days” that were not always so good for people like them.

Yet the steady march of change has inspired many other Americans to rethink their political identities. Most importantly, a new dimension of partisan conflict has emerged along the lines of formal educational attainment. Republican supporters in the electorate were once a consistently better-educated group than Democrats. But white voters with four-year college degrees have increasingly moved in a Democratic direction over the past two decades, while white voters who did not graduate from college have shifted even more dramatically toward the Republican Party. A growing “diploma divide” has rapidly reversed the traditional relationship between education and partisanship, now separating degree-holding white Democrats from degree-lacking white Republicans. These trends represent the largest and most consequential changes in the mass coalitions of the parties since the well-chronicled realignment of the formerly Democratic “solid South” during the mid-to-late twentieth century.

Historically, college graduates’ elevated collective wealth and social position encouraged them to prefer the relatively laissez-faire economic views of Republican candidates, just as the incentives of less prosperous citizens with more limited education once attracted them to a Democratic Party that presented itself as defending the material interests of the working class. Yet the shifting alignment between socioeconomic status and partisan preference among American voters has neither caused nor reflected a parallel change in either party’s fundamental economic philosophy. Party leaders and platforms remain strongly polarized today on matters of income redistribution, private sector regulation, and the provision of domestic social programs, with Democratic politicians continuing to stand on the left side of these issues and Republicans on the right.

The shifting alignment between socioeconomic status and partisan preference among American voters has neither caused nor reflected a parallel change in either party’s fundamental economic philosophy. Instead, other debates have become more central.

But as debates over other kinds of questions have become more central to American politics, college-educated and noncollege whites have been pushed in opposite partisan directions. The segment of the electorate that shares the respect for scientific expertise and comfort with social change now prevalent among white-collar professionals has come to feel alienated from a Republican Party where populist attacks on both educated intellectuals and liberal cultural values have become a foundational element of party doctrine, taking refuge instead among the increasingly welcoming Democrats. And noncollege whites who view contemporary social trends with suspicion have expressed their own disaffection by embracing a Republican Party that denounces the “radical transformation” of America – and by abandoning a set of Democratic leaders whom they associate with excessive cultural elitism.

Highly educated professionals are winning the culture

In the electoral arena, the two sides of this battle have become locked in an indefinite dead heat. American politics is now distinguished by a consistent pattern of partisan parity, producing very narrow national margins of victory and frequent reversals of party control in both presidential and congressional contests. While growing Republican strength among noncollege white voters appears to have recently provided the GOP with a relative structural advantage in the Electoral College and Senate races, both parties have won national power with roughly equal frequency since the early 1990s.

But the perpetually well-matched competition in American elections has not reflected a corresponding inertia in American society. Expanding our field of vision beyond the electoral realm shifts the picture from a persistent stalemate to an increasingly dominant liberal advantage. The growing population of well-educated citizens has drawn on its disproportionate social influence – within educational systems, mass communication industries, professional and charitable associations, and corporate management structures – to empower trained experts and lead a leftward shift in cultural values and institutional policies. Americans of all political persuasions are experiencing changes in their everyday lives that bear the imprint of this new technocratic bent and cultural zeitgeist, from diversity training mandated by their employers to climate change modules in their children’s science lessons. Conservatives have retained the ability to achieve regular electoral victories by harnessing popular discomfort with a swiftly changing world, but the broad social transformations they oppose are mostly beyond the power of elected officials to control. Policy complexification and cultural evolution have thus continued even during periods of Republican rule, while formerly apolitical spheres have become more politicized and nearly all social disagreements have acquired the flavor of an ongoing culture war.

Conservatives have retained the ability to achieve regular electoral victories by harnessing popular discomfort with a swiftly changing world, but the broad social transformations they oppose are mostly beyond the power of elected officials to control.

Culturally progressive technocracy, the governance of society by socially liberal and well-educated experts, is winning a long-term battle, reshaping the governmental, business, and nonprofit sectors – but not without stimulating a major backlash that has redefined conservative politics. As formal education levels have risen, increasingly determining citizens’ degree of economic success and position in the social hierarchy, they have furthered the expansion of expert-led policymaking while promoting the institutional adoption of left-of-center positions and practices on matters of race relations, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious pluralism, environmental regulation, public health promotion, and other major subjects of contemporary political disagreement. Political ideas and concerns within intellectual circles, including on college campuses, have migrated outward through political, media, corporate, and professional networks to dominate the national conversation, exerting visible influence on everything from the operation of typical Americans’ workplaces to the entertainment they consume once they return home. Rather than breeding consensus, the increasing power of education – and the educated – in American life has provoked a skeptical view of meritocracy within an ideological right whose mass base of support is mostly composed of white citizens without college degrees, fueling conservative distrust of cultural trendsetters and the institutions they control. The diploma divide is thus the product of a larger set of social transformations that have realigned the constituencies of both Democratic and Republican politicians, produced an imbalance in partisan deference to educated expertise, inspired new policy debates, polarized the media and information environment, and left few areas of American life free from political conflict.

The credentialed society

This account of political change rests on the foundation of two significant long-term trends in American society. The first trend is a substantial increase in collective educational attainment. This rise has been accompanied by growth in the financial rewards and enhanced social status achieved by the earning of a four-year college degree, along with the increased coupling of partners with similar educational experience. The second trend is a pronounced leftward shift in American cultural norms since the relatively conservative 1980s – a movement reflected in public opinion, government and corporate policy, the content of popular media, and the rhetoric and behavior of elites (a term we use descriptively, not pejoratively). Influential social institutions that are led by well-educated professionals and the creative class, including universities and school systems, the mainstream news and entertainment industries, and key segments of the nonprofit and corporate sectors, have mostly aligned with the liberal side of ongoing cultural conflicts.

But the combination of these two trends has also left whites without a college degree – who maintain relatively traditionalist predispositions, hold increasingly precarious economic positions, and perceive themselves as vulnerable to downward social mobility – open to populist appeals that promote resentment of, and mobilization against, members of the cultural elite like professional journalists, educators, scientists, and intellectuals. This counterreaction has not succeeded in reducing the advantages enjoyed by the well-educated or reversing the leftward trajectory of cultural life in America. But it represents a politically consequential rejection of dominant social currents by a large fraction of the national population, with recent manifestations ranging from the election of Donald Trump to the depressed COVID-19 vaccination rates in small towns and rural communities.

Advocating leadership by an educated upper-middle class distinguished by its disproportionate political efficacy and cultural influence has once again become fashionable.

Members of the American left, especially highly educated citizens engaged in political activism, have recently become more likely to identify themselves as “progressives.” This is an apt label in several respects. It reflects adherents’ support for fundamental changes to traditional policies and values in pursuit of a collective social benefit – the national “progress” that their political program claims to provide. But the term also contains a historical resonance, echoing the Progressive Era of the early twentieth century. The Progressives of that period envisioned an active government led by trained experts who would be empowered to apply their skills and knowledge to solve public problems, in tandem with social reform movements intended to improve the moral character of the masses. Advocating a similar combination of professional governance and larger social change, both led by an educated upper-middle class distinguished by its disproportionate political efficacy and cultural influence, has once again become fashionable in our own time.

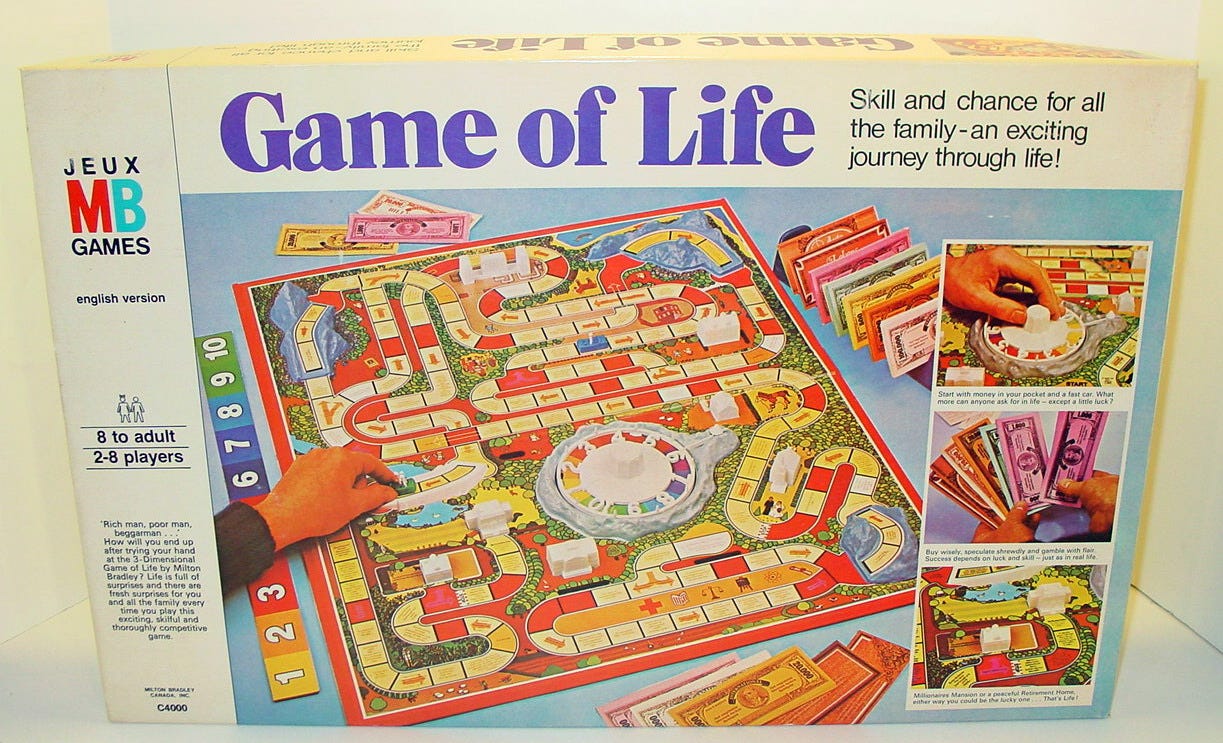

In the game of life, the choice of whether or not to pursue a university education determines one’s career and financial prosperity. Entering a lucrative occupation, such as medicine or accountancy, requires a college degree and affects a person’s entire future direction. At least, those are the rules in the board game version of Life. Its creator Milton Bradley did not believe that pure knowledge necessarily bestowed social respect, however: by the end of the game, players again face two possible paths – this time determining whether they “retire in style” as a successful millionaire or are relegated in their old age to being a poor philosopher. Although the crossroads in real American lives are rarely so stark, college attendance has become an increasingly important prerequisite for economic and social success. As careers requiring degrees proliferate and rise in relative status, the earning of a college diploma affects everything from romantic relationships to likelihood of incarceration to personal health and life expectancy.

But many people also maintain the skepticism toward a knowledge- and credential-based society expressed by Milton Bradley’s implied derision of intellectuals as lacking practical usefulness. The growing dominance of organizations and industries led by college and graduate degree-holders – and the accompanying promotion of socially liberal and cosmopolitan attitudes – has bred dissatisfaction among those who believe that American greatness was built by common sense, physical and emotional toughness, a strong work ethic, and respect for traditional ways. The quickening changes of contemporary life have not given equal deference to the wishes of all citizens or uniformly benefited every segment of the public. Americans are increasingly playing the game of life by a new set of imposed rules, but only some of them are pleased with where their path now leads.

This is an excerpt from Polarized by Degrees: How the Diploma Divide and the Culture War Transformed American Politics. Used by permission of Cambridge University Press.

Matt Grossmann (@MattGrossmann) is Director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research and Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University. A Niskanen Center Senior Fellow, he hosts the center’s Science of Politics podcast. David Hopkins (@DaveAHopkins) is Associate Professor of Political Science at Boston College. They previously co-authored Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats (Oxford University Press).

Image: Brett Streutker, Creative Commons license, https://www.flickr.com/photos/148686664@N06/44648211715