Moderation is not just an elite project

National policy solutions must be planted in local partisan soils.

Our book The Hollow Parties offers a shared diagnosis of both major parties—an incapacity to organize effective collective action that we call hollowness. This hollowness manifests in highly asymmetric ways between the parties—namely, Democratic ineffectuality and Republican extremism. And that asymmetry implies differing prescriptions for reinvigoration and renewal as well.

We bring to this task of renewing parties as civic actors an appreciation for a particular approach to politics that has gone into relative abeyance in the modern era, namely the grounded, pragmatically coalitional tradition in American political history that we call the “accommodationist” party strand. That emphasis leads our prescriptions to depart somewhat from the policy-forward bent of advocacy and reform that tends to predominate among think tanks like the Niskanen Center. At the same time, for Niskanen and its allied advocates of improved state capacity and an “abundance agenda”, we foreground the revival of moderate factions in both parties.

While top-down advocacy has its place, rooted operations with a healthy skepticism of purity politics—and an appreciation of what works in a given district— will more durably tap into voter sentiment and bolster moderate influence over party decision-making.

As a fractious center-left party grappling with education polarization and class dealignment, the Democratic Party faces a challenge that is clear enough notwithstanding its daunting scale. Renewal requires paring back the ever-encroaching network of Democratic-aligned but autonomous entities we term the paraparty blob. Simultaneously, Democrats must invest in the revival of subnational party organization and grounded civic actors (organized labor most especially) that can bolster the collective endeavors of a diverse coalition.

The relative absence of an organized moderate Democratic faction in the last decade is particularly notable for readers of this journal. In our view, the goal of party renewal would be better served by filling that gap with new commitments to local party capacity rather than with a new elite, national-level factional actor akin to the shuttered Democratic Leadership Council. While top-down advocacy has its place, rooted operations with a healthy skepticism of purity politics—and an appreciation of what works in a given district— will more durably tap into voter sentiment and bolster moderate influence over party decision-making. Even if candidates do not always campaign on precisely the policies that Niskanen favors, their openness to what works should ease the path to implementing those solutions.

The reality that right parties may be robust and civically rooted but also authoritarian—those MAGA boat parades have plenty of civic vitality—makes restraining their dangerous tendencies and ensuring their democratic loyalties all the more urgent.

On the Republican side, the path to renewal likewise entails civic revival, but the stakes of the endeavor are much higher, and the road far more trepidatious. When conservative parties succumb to extremist influence, democracy itself is vulnerable. Indeed, the reality that right parties may be robust and civically rooted but also authoritarian—those MAGA boat parades have plenty of civic vitality—makes restraining their dangerous tendencies and ensuring their democratic loyalties all the more urgent.

A programmatic strain of center-right reformism has long recurred in the GOP, informing the work of the 1960s Ripon Society, the Bush-era “Reformicons,” and present-day Never Trump redoubts like Niskanen. Such policy-minded projects across the decades have tended to follow patterns that put limits on their political purchase: a focus on national politics; a wariness of the grubby politics of give-and-take; and, above all, a difficulty identifying the social blocs that would plausibly serve as a base for their programs or the organizational forms the party might take to pursue them.

Read the whole series: Partisans without parties.

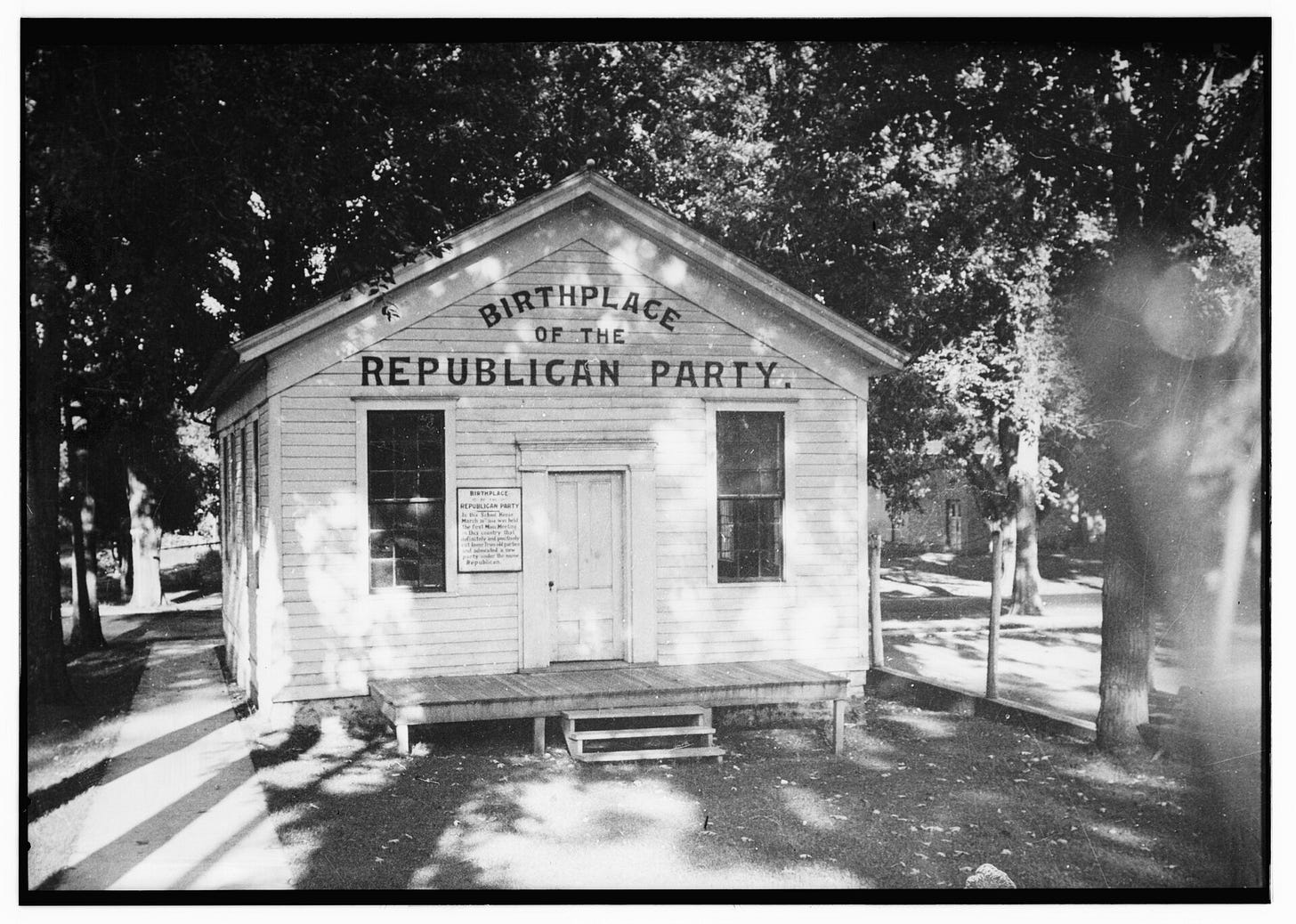

An alternative moderate tradition can be found in the pragmatic accommodationism of successful Republican politicians in the middle and later 20th century. The outlook of such partisans reflected their embeddedness in communities, and shaped the party at all levels of government. Theirs was a rolled-sleeve ethos of governance as problem-solving and social peacekeeping rooted in the milieu of their party’s base. Call it Blissism. Ray Bliss, the Akron-raised insurance man and legendary chairman of, respectively, the Ohio Republican Party and the Republican National Committee in the 1950s and 1960s, earned his reputation as an organizationally focused, “nuts-and-bolts” party-builder par excellence. But he was less a bloodless technician than a distinctly keen organizer of Republican politics in the accommodationist mode. In Ohio, he cross-checked voter registration rolls with membership lists for Kiwanis, Rotarians, country clubs, and chambers of commerce to identify the undermobilized ranks within the civic havens of midcentury Republicanism.

We see in that approach a viable center-right politics that performed constructive work for the political system. Rebuilding Republican organizations as a force safe for democracy depends on a broader revitalization of local civic life—a tall order indeed. But an updated version of Blissism offers the best route out of the linked pathologies of rule by donors and rule by demagogues.

Daniel Schlozman is associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University. He is the author of When Movements Anchor Parties: Electoral Alignments in American History.

Sam Rosenfeld is associate professor of political science at Colgate University. He is the author of The Polarizers: Postwar Architects of Our Partisan Era.