From stakeholder capitalism to state-capacity capitalism

How business helped fix dysfunctional government once — and can do it again.

There are longstanding debates about the role of the state in capitalist democracies, particularly around the need for, and amount of, state intervention in markets. Polarization and gridlock have amplified problems related to 50 years of state retrenchment, with growing frustration over perceived failures of governance in the United States. Neoliberal orthodoxies are therefore giving way to a renewed intellectual ferment regarding the role of government in American life.

On the one hand, there has been a renaissance in thinking about the state as a tool of economic policy, discarding minimalist approaches to regulation and redistribution in order to improve the lives of a public clearly dissatisfied with the status quo. President Biden has embraced industrial policy, and conservatives such as Mitt Romney and Marco Rubio have advocated social policies like tax credits and transfers. These new policy ideas, however, have yet to translate into meaningful partisan alignments.

And in a darker trend, the state increasingly is being understood as a tool of political combat. A growing extremism rejects the possibility and even desirability of a neutral bureaucracy. Officials serving apolitical functions, including election administrators, public health officials, attorneys at the Department of Justice, and internal revenue service agents have had their roles questioned and politicized. With Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, the democratic process itself has come under threat.

This movement to undermine the functioning of the state in pursuit of political ends is increasingly focused on programmatic details. Meanwhile, the movement to improve the functioning of the state in the market economy is happening mostly at the big-ideas level, with insufficient attention paid to execution. There is no clear coalition for investing in government per se — in the administrative institutions, bureaucratic agencies, and public sector workforce that provide the basic infrastructure to make and implement policies.

The business community may seem like the last place we should look for leadership of such a coalition. Since the 1970s, organized business has been the foremost voice advocating for government retrenchment. Through lobbying, campaign finance, and national associations like the United States Chamber of Commerce, corporate America has backed a policy agenda of deregulation and privatization, shrinking the scope of government and expanding the scope of the market.

A historical perspective helps us understand how capitalists can embrace long-termism in times of democratic turmoil.

But this approach is no longer sustainable. Contemporary capitalism has fueled inequality, as well as perceptions that government serves the interests of economic elites. Economic discontent manifests politically, and business leaders are increasingly drawn into social and political conflicts. Democratic instability has economic consequences, with businesses concerned about political retaliation, stable investment, and rule of law.

What role does business play in rethinking the state’s role not only in the economy, but in democracy more broadly? In the late nineteenth century, industrial capitalism spurred the rise of sectors such as transportation and manufacturing, and the towns and cities of the nation became better connected and integrated. Politics, however, remained parochial and corrupt, and the state was an important tool of political competition, as loyal partisans were offered jobs or cash in exchange for delivering voters to the polls. It was a party system ill-suited to the kind of complex regulation and long-term policy the new economy required. Businesses exploited the corrupt environment for their own short-term gains, but also realized that ineffective governance would hamper them in the long run.

Building state capacity can protect the state from politicization and shape a capitalism for the future—one more attentive to workers, consumers, and broader social goals beyond growth alone. A historical perspective helps us understand how capitalists can embrace long-termism in times of democratic turmoil.

The triple squeeze on business

Since the 1970s, business has engaged in open conflict with “the state,” broadly speaking. And in response, the state has been dramatically sed down. The United States bureaucracy is understaffed, under-resourced, and dogged by proceduralism and reliance on contractors. Public confidence in government is also at historic lows, the unsurprising result of decades of anti-state rhetoric. Politicians from both parties have been eager to tout ways that they have constrained the state. Republicans have emphasized a policy agenda of deregulation, slashing corporate and personal taxes, and privatizing government services. Democrats have embraced, albeit to lesser degrees, welfare reform, deregulation, and privatization.[1] The perception of government ineffectiveness then justifies further efforts to limit state capacity, perpetuating a problem of under-investment.

Now, we face a long list of seemingly intractable problems that the government, even working with the private sector, has been hard-pressed to solve. The cost of living—particularly basic needs of housing, childcare, and health care—has significantly outpaced incomes and inflation. Many communities are suffering from lower life expectancy and deaths of despair. While globalization, trade, and advances in the so-called knowledge economy have driven growth, many American workers are excluded from these gains, with fewer job opportunities and less job security. The erosion of faith in government spills over to dissatisfaction with democracy and provides a pretext for anti-system leaders to come to power.

Models like “stakeholder capitalism” have neither solved our major problems nor curbed the backlash. Instead, they have made businesses even more vulnerable to demands from activists on the left and the right.

This state of affairs squeezes business in three ways. First, the pressure on business to be attentive to social issues has mounted in recent years as trust in government has declined. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, Americans trust business more than they trust the media or government, and they want companies to do more to address problems like climate change and economic inequality. Employees, in particular, expect their companies to formulate political responses and show "societal leadership."

This is a natural instinct, and one that corporate leaders themselves have embraced. That is, they have thought about changing capitalism, rather than changing politics. Larry Fink, who heads the investment giant BlackRock, outlined this vision of stakeholder capitalism first in a letter to CEOs in 2014, and in a letter to shareholders in 2018. Taking a view of stakeholders requires being attentive not only to profits, but to the interests of society; corporations should, according to Fink, recognize the many relationships between corporations and the "employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper."

The Business Roundtable, meanwhile, issued its new statement on the purpose of the corporation in 2019. Led by JP Morgan Chase head Jamie Dimon and signed by 181 CEOs, the statement noted that the American dream is "fraying," and that corporations need to be more attentive to factors like employee compensation, ethics in supply chains, and supporting sustainable practices in order to benefit society overall—not just the corporate bottom line. Many CEOs have been outspoken on the need to think more holistically about the distributive and societal consequences of contemporary capitalism, including Marc Benioff of Salesforce and Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates. Even the United States Chamber of Commerce has initiated projects to solve capitalism from within, by championing board diversity and “environmental, social, and governance” goals and acknowledging the "shortcomings" of capitalism—and warning of populist backlash against business.

The stakeholder movement has been accompanied by a new fervor around corporate social responsibility, in particular the uptake of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals for corporations. ESG goals are not clearly defined; rather, they are a somewhat subjective set of standards or concerns to which corporations should commit themselves. Because there are not institutional means of holding corporations accountable, watchdog organizations, journalists and quasi-regulators have instead been monitoring corporate speech and actions. Nasdaq, for instance, received approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission to implement a board diversity rule for its listings. Activist shareholders are also rallying around ESG goals.

But this agenda has neither solved our major problems nor curbed the backlash. Instead, it has made businesses even more vulnerable to demands from activists on the left and the right. In fact, Republican-led state governments have passed laws restricting assets they control from being invested along ESG principles or retaliating against companies allegedly pursuing investing “boycotts” (e.g., in firearms or fossil fuels).

If business leaders are not to remain trapped between their cultural and economic agendas, the path forward may lie in rethinking the role of the state.

That leads to the second big problem for business: the fraying of the decades-long alliance between corporate America and the Republican party. This alienation has been driven by the far-right faction associated with President Trump, and new tensions over the democratic process, socio-cultural issues, and instability in policymaking. During President Trump’s time in office, business became more willing to speak out against government action—such as draconian immigration policies—as well as government inaction, on issues such as gun control or climate change. Businesses were vocal supporters of the fights for racial justice, voting rights, and reproductive rights. They now find themselves in the paradoxical position of funding Republicans who will implement favorable economic policies while also denouncing their social and cultural positions.

Republican politicians, in turn, have been quick to denounce “woke capitalism.” Mitch McConnell condemned the responses of corporate America to state voting bills, recommending instead that businesspeople stay out of politics (but continue their campaign donations). Republican politicians such as Senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley have sworn off corporate PAC money. And Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis launched his high-profile battle with Disney over the state’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the malaise that helped fuel the rise of populism threatens the public goods on which business relies. Slower innovation and productivity gains, failure to reduce the risk from climate change, and deep social ills do not bode well for growth.

Beyond partisanship, businesses overall are also responding to a resurgent labor activism across sectors, and a backlash to the precarity and poor working conditions associated with a globalized economy. Managing industrial relations has long been the purview of the state, not of markets alone. Economic conditions create political demands, ones that political leaders must resolve—and corporations are wise to realize that sooner, rather than later.

If business leaders are not to remain trapped between their cultural and economic agendas, the path forward may lie in rethinking the role of the state.[2] President Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for 2024, is campaigning on a vision of a state beholden to individual power. One of his final acts as president in October 2020 was an executive order, known as Schedule F, to reclassify many civil service employees as political appointees. They would be exempt from protections against politicized hiring and arbitrary dismissal. On the campaign trail, President Trump has gone further to explain how he would wield the state against his opponents and against the media. Many of President Trump’s former staffers, working with the Heritage Foundation and its Project 2025, are assembling lists of bureaucrats to replace career civil servants as part of a ploy to dismantle the so-called Deep State.

Politicizing—even weaponizing—the state for political ends marks a dangerous turn in our democracy, with costs to those who rely on effective delivery of services and impartial application of the law. Business, in particular, needs a state that can perform its basic regulatory and administrative responsibilities, enforce contracts, and uphold the rule of law. While democracy requires that elections result in policy change if they are to be meaningful, markets require stability across elections. This stability comes in the form of a bureaucracy that operates neutrally, discreetly, and reliably—and, critically, without political interference.

Lessons from history

Politicians are reluctant to take up the mantle of state reform when there is no clear electoral reason to do so. Historically, reforms like the establishment of a meritocratic civil service or laws against corruption and patronage required what Martin Shefter termed a “coalition for bureaucratic autonomy,” composed not only of elected officials but importantly of those interests “who wanted to protect state resources from plunder or streamline the working of government.”[3] These interests valued “universalism,” rather than discretion and particularism, in the way government allocated services. Shefter noted that these groups may have wanted the state to be neutral with respect to individuals, but not necessarily with respect to groups. In other words, those who valued universalism wanted a state that could act uniformly and predictably—but often also wanted states to protect some interests over others. It was not mutually exclusive for a state to operate neutrally (with respect to politics) while also tending to serve economic interests.

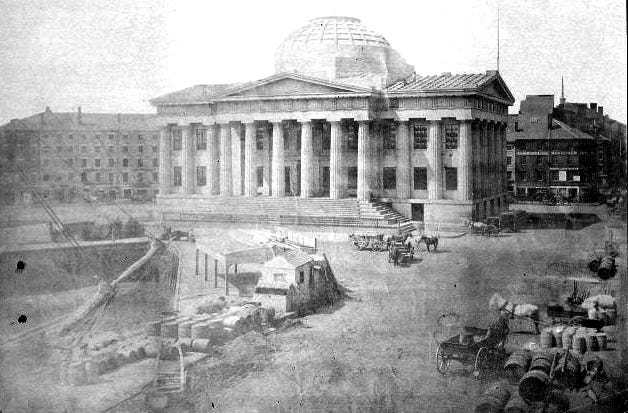

Examining corruption in the nineteenth century can tell us something about how functioning states come about. In the late nineteenth century, leaders of corporations in the new industries of railways, steel, and oil routinely bought off state and national politicians. This corruption arose against a backdrop of patronage politics—the “spoils system” that arose in the Jacksonian era, as the suffrage expanded and partisan competition heated up. The spoils system became entrenched in American nineteenth-century politics, with parties promising government favors and jobs to their political supporters. Party members in turn provided financing and labor for the parties, especially by mobilizing voters at election time.

Patronage existed at all levels of government. The election of new presidents entailed turnover in the federal civil service (e.g., post offices and customs houses) because of presidential patronage appointments. In cities, patronage was fundamental to the growth of political machines, which secured power by granting favorable jobs and contracts to those loyal to the party. While patronage was an effective way for parties to cultivate support, it fostered predatory state institutions that operated according to political logic. The bureaucratic apparatus of the state existed primarily to help parties maintain power, rather than to provide governance and administer policy. There was a growing divergence between whom the state served—a narrow set of politically connected players—and what society required as the industrial economy expanded.

In this climate, the technocratic and efficient values of the rising managerial corporation were the same values that business leaders increasingly advocated for government as well. At the inaugural convening of the National Manufacturers Association in 1867, members bemoaned the costs of government in the form of “expensive rogues” and the need for “the most radical revolution in the character and capacity of the public service.” The Association declared that it “heartily approve[s] the Civil Service bill” that had been proposed in Congress, and decried “the dangerous custom of giving public posts to political paupers and partisan servants, regardless of their fitness.”[4]

Business leaders called patronage a "stench in the nostrils of the people of this country," and contrasted it with their principles of "professionalism, efficiency, and transparency.”

In the 1870s, business leaders from across the country convened the National Board of Trade, a cross-sectoral trade association. In the decades prior to the formation of this first attempt at national business association, a growing commercial class consisting of small manufacturers, wholesalers, shipping merchants, and others organized into local chambers of commerce and boards of trade. The national organization aimed to articulate shared commercial interests and to "position merchants as stewards of an economic commonwealth."[5] In their early meetings, representatives from industrial and financial companies noted that the federal government seemed ill-equipped to govern trade, transport, and similar needs of an integrated national economy. They noted in particular the drawbacks of patronage, which created unpredictability in policymaking and "entailed vast losses" that put merchants and manufacturers at risk of failure. The business leaders called patronage a "stench in the nostrils of the people of this country," and contrasted it with the principles of "professionalism, efficiency, and transparency" that prevailed among businessmen.[6]

In order to create "efficiency and purity in the administration of public affairs," the National Board of Trade called for an end to partisan appointments to government offices. They also demanded national oversight of industry in order to preempt differing state approaches, particularly over transportation prices.[7] As the nation became more industrialized, businesses sought to expand their commercial activities both at home and abroad: as a result, they needed more efficient and predictable delivery of services from government. These industrial interests were an important force in the nation’s political economy, even if their record was eclipsed by the monopolies and large corporations of the Gilded Age that were responsible for high-profile corruption scandals in many states, as well as during the Grant administration.

The nascent movement for civil service reform capitalized on a reform ethos associated with an industrializing society; the historian Ari Hoogenboom explains that “civil service reform flourished in an age when the businessman, particularly the industrialist, became the most important element in American society.” Industrialists were not on the front lines of reform—instead, reformers were more often drawn from a professional class of lawyers, editors, or merchants from established families—but the idea that government needed to serve interests other than naked political or partisan goals was associated with economic growth and increased trade.[8] A set of political reformers interested in curbing corruption—by taking on problems associated with party machines and graft—advocated new hiring and promotion practices in the civil service, drafting legislation as early at the 1860s. Reformers also invoked business principles—those being articulated by nascent collective business interests—that included efficiency and fairness. After leading an investigation into patronage and corruption in the New York customs-houses, the politician John Jay enumerated the millions of dollars in lost revenues—and called for “placing the business of government on a business footing.”[9]

President Garfield was assassinated in 1881 by Charles Guiteau, who had sought a civil service placement. A month later, a group of lawyers, editors, clergymen, and professors (later joined by businessmen) created the National Civil Service Reform League. Many of its members, including George William Curtis (editor of Harpers’ Weekly), Carl Schurz (former Secretary of the Interior, editor of the New York Evening Post), E. L. Godkin (editor of The Nation), and Dorman Eaton (lawyer) had studied and reported on civil service reforms in other countries, or took part in presidential commissions to investigate pathways for reform. They had long advocated the use of meritocratic and competitive examination for positions in a depoliticized civil service. They turned civil service reform into a national issue, writing editorials about its urgency and organizing in states and cities. By the 1880s, businessmen were a growing segment of the coalition in favor of reform, with the New York Times reporting in 1881 that “only lately…[have] businessmen in considerable numbers been drawn toward” a movement once dominated by journalists and professionals.[10] Not only were businessmen working in commerce and finance more likely to interface with customs officials, but they also saw a need to ‘clean up’ government in the face of monopolistic industries.[11]

When Chester Arthur assumed the presidency, he vowed to pass civil service reforms, but failed; in the 1882 midterms, the Democrats retook the House majority. With the public increasingly mobilized in favor of civil service reform, Republicans and Democrats passed the Pendleton Act in 1883.[12] In his inaugural address in 1885, two years after the Pendleton Act’s passage, President Arthur promised to enforce the reforms on the grounds that “the people demand reform in the administration of the Government and the application of business principles to public affairs.”[13]

The Pendleton Act created a Civil Service Commission to administer examinations and create rules for the civil service.[14] It eliminated undue influence of legislators in appointing individuals to civil service jobs, and also banned civil servants from coercing colleagues to engage in political activities. The Pendleton Act only applied to 10 percent of the federal workforce when initially implemented; by 1920, its scope had expanded to over 80 percent of the federal workforce. The Pendleton Act created classified positions, which were subject to competitive examination and protected workers from arbitrary dismissal. Upon passage, the Act applied to postal workers (which constituted 34% of the federal workforce), as well as customs houses and the federal clerical workers in Washington, D.C. The Act rolled out classified positions by size of workforce, initially applying to post offices employing over 50 people. Successive presidents expanded the classified federal workforce—by 1893, for example, all post offices with free delivery were subject to reform provisions.[15]

While it is difficult to determine the role that interests, broadly construed, played in passage of the Act, the National Boards of Trade and the 1895 formation of the National Association of Manufacturers argued for cleaning up the government—for getting rid of “jobbery” and corruption. After passage of the Pendleton Act, Senators read letters from local businessmen denouncing the poor quality of mail delivery in places ranging from Kansas to New England.[16] When the National Association of Manufacturers convened in 1896, they argued for the consular service at the Department of State to be “treated upon a business basis…maintained upon strictly business principles,” with no political consideration and “more liberal remuneration.”[17] Both groups’ noted their efforts to petition Congress and meet with members to press for government reforms.

Business and political reform advocates alike stressed the disconnect between the needs of the industrial economy and the capabilities of the government. The politicization of bureaucracy, in particular, was seen as outdated, if not actively corrosive—it no longer aligned with the values of public service, nor did it help to streamline the delivery of much-needed government services.

By the 20th century, demands for better governance became integrated into the broader Progressive reform movement, alongside calls for labor protections and regulation of industry. Business support for the expansion of state authority continued into the Progressive era, though it was by no means homogenous or universal. Beyond the railway and steel robber barons that dominate the history of this era were financiers and bankers, lawyers, merchants, and leaders in burgeoning industries like food and chemical processing who were invested in articulating the role of government. They supported hiring experts and deepening scientific expertise in executive agencies,[18] and reining in laissez-faire excesses through federal regulation.[19] Letting governments take on the responsibility of setting rules and standards allowed companies to operate within predictable parameters.

Cities, in particular, became particularly important sites of political contestation over questions of state capacity. In 1840, about 12% of the American population lived in cities; by 1890, that number had risen threefold as the economy shifted from agriculture to industry.[20] Muckrakers exposed the disease, poverty, and hazardous working conditions plaguing urban residents. But elected officials were ill-equipped to manage these new problems. Instead of providing massive infrastructure and public goods, political machines relied on patronage to award jobs and contracts, and politicized the distribution of services and benefits.

The National Municipal League organized across cities of the United States, and many local business leaders became active in municipal reform efforts. The NML and other good government organizations wanted to reduce the influence of party machines, and instead rely on experts to solve public problems. They also emphasized that government needed to take on new responsibilities given the scale of problems facing cities. Sanitation, streetlights, paving roads—these were increasingly seen as public goods the government needed to provide.

Business leaders advocated reform of cities not because they were so public-spirited, but because they understood that forming individual relationships with politicians would do little to guarantee that the overall urban environment would facilitate economic growth.

Local governments expanded into services such as waste collection and public transportation, and worked with local communities in the provision of hospitals and schools. Business leaders and civic reformers undertook campaigns for public goods such as libraries and parks and supported nascent social policy around health and housing.[21] Reformers often sought to apply business principles to government itself. Sometimes this took the form of prioritizing new values, like efficiency or scientific approaches to problem-solving, over partisanship or personalism. There was also institutional transformation, such as a charter movement that advocated nonpartisan councils and managers to govern cities. Business leaders advocated these reforms not because they were so public-spirited, but because they understood that forming individual relationships with politicians would do little to guarantee that the overall urban environment would facilitate economic growth. Rather than one-off favors, they sought urban development that would help the workforce and create more liveable, productive cities.[22]

A civil service insulated from patronage and corruption was crucial to the success of democracy and capitalism. It required political parties to agree that effective state capacity outweighed the political benefits of patronage.[23] The spoils system, though politically beneficial to parties, was becoming too costly—both in terms of public disapproval and economic inefficiency—to maintain. The sequenced expansion of merit-based hiring allowed the national parties to claim credit for civil service reform, while slowly phasing out patronage practices. By the Progressive Era, reformers also sought to eliminate corporate contributions in politics, and to depoliticize the civil service through the Hatch Act. A study of the Pendleton Act found that in the years after its passage, postal delivery errors declined, productivity of mail carriers rose, and local partisan paper circulation declined—all indicating expanding state capacity and declining party machines.[24]

Ultimately, the demise of the patronage system facilitated programmatic politics, whereby parties became primarily associated with policy agendas rather than with the distribution of specific favors. At both the local and national levels, parties expanded the administrative responsibilities of the state so that they could credibly commit to policy implementation. Party competition no longer involved the plunder of state resources any time there was turnover in government. Instead, leaders were held accountable based on the promises they made to voters, ushering in a new era of democratic governance.

Realignment and the future of business and democracy

Today, a half-century of neoliberal economic orthodoxy underpinning globalized, financialized capital has created an unsustainable combination of unresponsive democratic government amidst worsening social and political conditions. Corporations and businesses have been deeply invested in maintaining an economic agenda favorable to capital but are also being pressured to develop responses to political and economic problems. Businesses once again need to rethink their interests, broadly construed, and to realize that the pursuit of economic advantage alone may not be in the long-term interests of democracy and growth. Large corporations can afford to stake out political positions in ways small and mid-sized companies cannot and may be better equipped to handle more regulations or higher tax burdens, so it may be the case that the business community fractures when it comes to issues of greater state capacity. While they historically enjoyed a closer relationship with the Republican party, corporate interests do not align clearly with the interests of the far right. Businesses have also long cultivated Democrats, and workers and managers in new sectors such as technology and clean energy are likely to be more ideologically aligned with the left.

The current combination of polarized parties, a weak state, and citizen demands for policy redress will require new political coalitions to resolve. In particular, parties will need to articulate and channel the demands of specific segments of the electorate whose interests are not well-represented. It is up to the parties not to prioritize their relationship to capital, but instead to channel the needs of the electorate—and to develop programs based on addressing those needs. As parties think more deeply about policies to govern the future, they will also need to build a state that is well-resourced and staffed, and therefore able to implement those policies in ways that rebuild trust in government.

Businesses once again need to rethink their interests and to realize that the pursuit of economic advantage alone may not be in the long-term interests of democracy and growth.

Capitalism and democracy work best when they work together, rather than when they are at odds; historically, capitalists have relied on elected leaders to build strong state institutions required for growth and to provide democratic oversight of markets. Meanwhile, capitalism cannot solve, nor should it solve, political problems generated by economic change.

The problems of patronage and monopoly from the Gilded Age may not map perfectly on to the problems we face today. But the broad themes resonate. In the past, economic changes—particularly large-scale changes brought on by industrial capitalism—created new political demands. Importantly, these political demands were not just those related to competing social and economic policies. One of the foremost demands was for better governance itself, and a reorientation of the state away from patronage and towards technocratic competence and new administrative responsibilities. Developing state capacity required compromise among politicians and business leaders to forfeit short-term material or political advantage in favor of long-term stability and growth. Business today can play a role in agreeing to similar political compromises, and in articulating how robust parties and a strong state can solve the problems that the private sector cannot.

Didi Kuo is a Center Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) at Stanford University. At Stanford's Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), she oversees the Program on American Democracy in Comparative Perspective. She is the author of “The Great Retreat: How Political Parties Should Behave and Why They Don’t” (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) and Clientelism, Capitalism, and Democracy: The Rise of Programmatic Politics in the United States and Britain (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[1] On the Democratic embrace of neoliberalism see Stephanie Mudge, Leftism Reinvented: Western Parties from Socialism to Neoliberalism; Lily Geismer, Left Behind: The Democrats' Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality.

[2] Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson, Conflicted Consequences (Center for Political Accountability, 2021).

[3] Martin Shefter, “Party and Patronage: Germany, England, and Italy,” Politics & Society 7, no. 4 (1977).

[4] The New York Times, “Manufacturers’ Convention,” May 27, 1868.

[5] Cory Davis, “The Political Economy of Commercial Associations: Building the National Board of Trade, 1840–1868,” Business History Review 88, no. 4 (2014), 762.

[6] Didi Kuo, Clientelism, Capitalism, and Democracy (Cambridge UP, 2018).

[7] Robert Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (Macmillan, 1967).

[8] Ari Hoogenboom, Outlawing the Spoils, University of Illinois Press (1961); see also Ari Hoogenboom, “Thomas A. Jenckes and Civil Service Reform,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review vo. 47, no. 4 (March 1961), pgs. 636-658

[9] John Jay, “Civil-Service Reform,” The North American Review 127, no. 264 (Sept-Oct 1878), p. 285-6.

[10] Quoted in Hoogenboom 1961, p. 195.

[11] An earlier historical interpretation of civil service reform comes from Matthew Josephson in The Politicos (1938). Josephson argued that industrial capitalists supported civil service reform precisely so they could displace patronage workers as sources of campaign financing and disempower politicians.

[12] See Sean M. Theriault. “Patronage, the Pendleton Act, and the Power of the People.” The Journal of Politics 65, no. 1 (2003), 50–68.

[13] Chester A. Arthur Inaugural Address, 1885.

[14] Paul Van Riper, History of the United States Civil Service (1958).

[15] Abhay Aneja and Guo Xu, “Strengthening State Capacity: Civil Service Reform and Public Sector Performance During the Gilded Age,” American Economic Review (forthcoming, 2024). Customs officers, on the other hand, made up only 3% of the workforce.

[16] Fred. Perry Powers, “The Reform of the Federal Service,” Political Science Quarterly vol 3. No 2 (June 1888), p. 270-271.

[17] “Purposes of the National Association of Manufacturers,” 1896, Digital archives, Hagley Library.

[18] Jesse Tarbert, When Good Government Meant Big Government: The Quest to Expand Federal Power, 1913–1933 (Columbia UP, 2022).

[19] Laura Philips Sawyer, American Fair Trade: Proprietary Capitalism, Corporatism, and the 'New Competition,' 1890–1940 (Cambridge UP, 2018).

[20] Alexandra W. Lough, "Politics of Urban Reform in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 1870-1920," American Journal of Economics and Sociology 75, no. 1 (2016).

[21] Daniel Amsterdam, Roaring Metropolis: Businessmen’s Campaign for a Civic Welfare State (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

[22] James Rauch, “Bureaucracy, Infrastructure, and Economic Growth: Evidence from U.S. Cities during the Progressive Era,” American Economic Review 85, no. 4 (1995), 968-79.

[23] Barbara Geddes, Politician's Dilemma: Building State Capacity in Latin America (1996);

Anna Grzymala-Busse, Rebuilding Leviathan: Party Competition and State Exploitation in Post-Communist Democracies (2007)

[24] Aneja and Xu, “State Capacity,“ 2024.