After almost a year packed with news about mass layoffs, “voluntary” resignations, and early retirements, the effects of the Trump administration’s campaign to remake the federal workforce are coming into focus. The total impact of headcount reductions for 2025 is around 300,000 positions on net, according to the Director of the Office of Personnel Management. This would put the federal workforce at around 2 million to 2.1 million at the end of 2025 – a reduction of 10-15 percent, primarily achieved through voluntary separations and early retirements. In other words, for the first time in a while, this chart will look a little bit different next year:

Many Americans would be surprised to learn that the federal workforce has remained remarkably stable since the late 1960s, fluctuating between 2 million and 2.3 million employees. As a result, the size of the civil service has decreased dramatically as a percentage of the population, even though it does a lot more today than it did in the Johnson administration. The federal bureaucracy, in other words, has already been doing more with less for decades. A headcount reduction of the magnitude we saw this year, however, is almost unheard of – almost.

As the chart suggests, this is not the first time Americans have indulged the fantasy of running a modern state on an even smaller headcount. The 1990s saw reductions at a similar scale to 2025’s (albeit spread out over many years), and that period has much to teach us about what the public can expect this time.

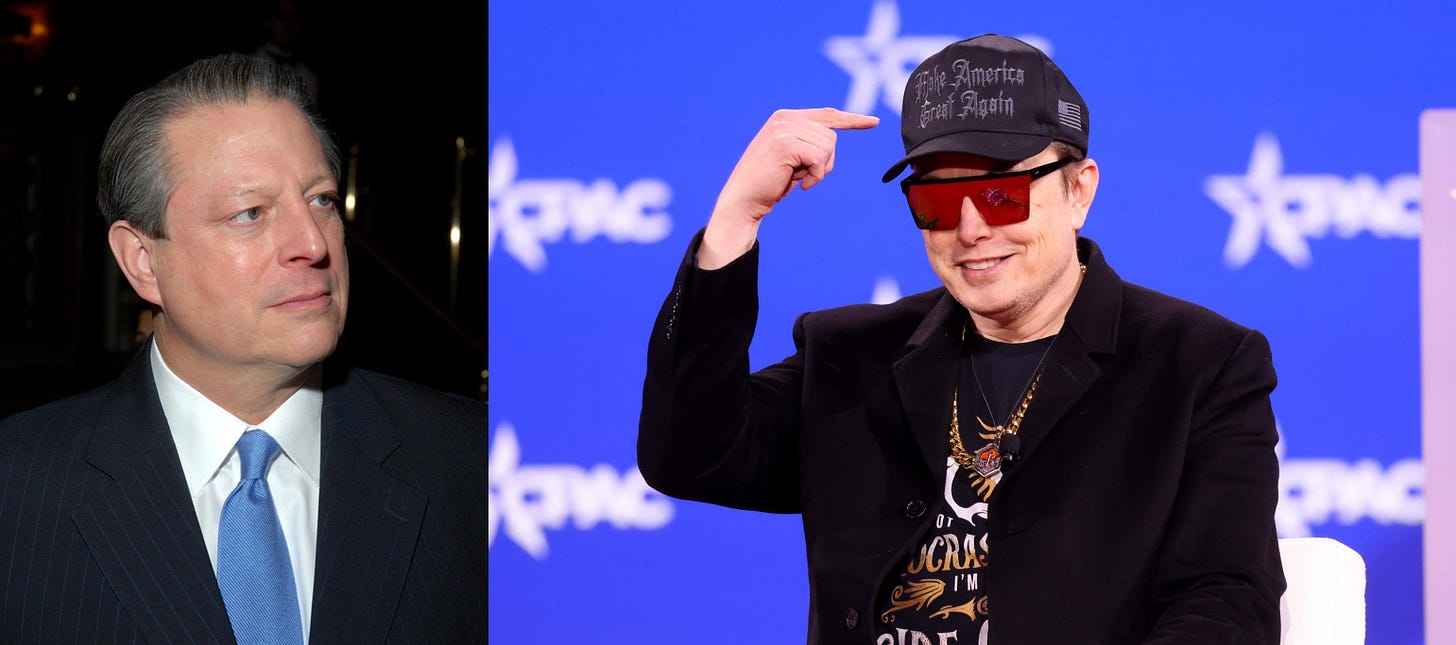

Thirty years before Elon Musk arrived in Washington, Bill Clinton began his first term by assigning Al Gore to lead an initiative aimed at “reinventing government.” This multi-year effort focused on shrinking the federal workforce, improving efficiency, and positioning the government for the post-Cold War era. From 1993 to 1998, the National Performance Review (NPR) and the National Partnership for Reinventing Government (the latter incorporating the former) pursued this vision with notable results — by 2000, the government looked and functioned very differently compared to 1992.

Reinventing Government has served as a convenient foil for both critics and defenders of the Trump administration’s “efficiency” push. Critics from the left point out that Clinton’s effort proceeded more methodically, involved Congress, and tried to treat federal workers with dignity — all values that this White House appears to eschew in favor of swinging the hammer and just seeing what breaks. On the other hand, defenders from the right point out that the Clinton administration successfully reduced the federal workforce by 400,000 people, or about 20 percent of the civilian workforce, through many of the same mechanisms that the Trump administration is now employing, such as layoffs (or Reductions in Force in the jargon of government).

But if the outcome we are focused on is effective government, both narratives miss the point.

Clinton obeyed red lights while Trump is speeding through them, but both paths lead into the same trap. Both administrations became overly focused on headcount as their measure of success and (in the process) started making many choices that undermine the government’s long-term state capacity.

The Clinton administration had good ideas about reform

In the classic diagnosis of the Clintonites, the federal government of 1993 was procedurally bloated and full of middle management that did little to advance agencies’ missions. Writing in 1993, the National Performance Review diagnosed the problem this way: “Is government inherently incompetent? Absolutely not. Are federal agencies filled with incompetent people? No. The problem is much deeper: Washington is filled with organizations designed for an environment that no longer exists.” It added: “The federal government is filled with good people trapped in bad systems: budget systems, personnel systems, procurement systems, financial management systems, information systems.”

The idea was to improve the government’s ability to deliver by reducing red tape, providing federal employees with more flexibility, partnering with the private sector where it had more expertise, and moving to more ‘performance-based’ approaches to carrying out the business of government. If this sounds like it rhymes with the work of contemporary critics like Ezra Klein or my colleague Jen Pahlka, that’s because it does. Much of the Clinton administration’s diagnosis still rings true today. One could imagine this line from the NPR’s report being pulled from a New York Times op-ed discussing the Biden administration’s rural broadband program: “It is almost as if federal programs were designed not to work. In truth, few are ‘designed’ at all; the legislative process simply churns them out, one after another, year after year. It’s little wonder that when asked if ‘government always manages to mess things up,’ two-thirds of Americans say ‘yes.’”

This critique was basically correct in 1993, and it remains so in 2025. Which begs the question: If the federal government figured this out 30 years ago, why are we still in the same place?

“The era of big government is over”

Notwithstanding the official rhetoric about good people in bad systems, underlying the NPR’s argument was a very dim view of the (at the time) 2.1-million-person federal workforce and its role in hindering efficient government. Bob Stone, who directed the effort, expressed this position in stark terms:

Roughly one of three federal employees had the job of interfering with work of another two. We called them the forces of micromanagement and distrust, and we wanted to reduce the number of inspectors general, controllers, procurement officers and personnel specialists.

The thinking was that if a significant portion of the federal workforce was mostly serving as an obstacle, it was worth shedding their jobs entirely. Congress, agreeing with this view, granted the Clinton administration the authority to make the cuts legally and expeditiously. By the end of the decade, the Clinton team reckoned they had managed to reduce the federal workforce by 426,000 jobs. Taken at face value, this approach is completely reasonable. If a third of the federal workforce is doing nothing to add to mission effectiveness, and if you could reorganize to be successful without them, then reducing the size of the federal workforce by 20 percent seems like a great first step. To its credit, the administration set about doing just that.

However, political and practical realities asserted themselves. The president, wanting to promise something tangible and measurable to show progress, walked into the Capitol for the 1996 State of the Union and declared: “The era of big government is over.” He promised to cut the size of government by several hundred thousand people. In making that commitment, however, he turned a useful measure of transformation (savable headcount) into a target (roles cut). The critical step of achieving larger programmatic reforms to keep things running with a smaller workforce dropped out of the conversation. From there, the old management heuristic that “when a measure becomes a target it ceases to be a good measure” insisted on its rightness again.

Some of this is Congress’ fault. Leaders on the Hill got behind the administration’s effort to cull the workforce, but did not uphold their end of the bargain. The personnel cuts were supposed to be downstream of program reform; instead, they ended up coming first and the reforms never materialized. As John Kamensky, the Deputy Director of the NPR, wrote in 2020:

The ‘thoughtful’ cuts did not happen as envisioned. Congress intervened, mandating cuts at a faster pace, without providing the flexibility envisioned by streamlining personnel or acquisition requirements.

This meant that agencies were left scrambling, trying to figure out how to reduce headcount without the ability to actually de-proceduralize the work. To minimize the damage, agencies were forced to eliminate positions that they felt they could make do without or easily outsource. That meant either eliminating entire functions or trimming large numbers of junior, clerical, and administrative roles that could be replaced by contractors or were primarily intended to prepare new hires for more challenging work.

Cutting the jobs, leaving the red tape

Process reform was an afterthought. Most of the signature changes to the process were cosmetic at best or operationally-challenging at worst. Take the Byzantine world of federal human resources. As Jeff Neal, a former HR leader at DOD and DHS argued, the reforms:

…gave recruiting authority to agencies, but made them follow a 350-page OPM Handbook.…It eliminated the [Federal Personnel Manual], but kept the complex regulations and eliminated many of the OPM staff who were the real experts who could explain all those regulations. Not to worry – agencies had HR experts who could help. At least they did until the NPR cut them by half, leaving federal HR offices unable to do anything but the most essential work. The initial ideas of the NPR may have been sound, although the original report had a lot of snarky anecdotes. But, at least with respect to federal HR, the NPR was a half-baked set of reforms that broke the mold and did not put something functional in its place.

By only going halfway and adopting a cut-first approach without a plan to meaningfully transform the entire system, the Clinton team wound up hobbling the HR enterprise rather than reforming it.

At the same time, the administration made several logical but shortsighted human capital management choices. To hit its aggressive reduction targets, it used blunt instruments like voluntary buyout offerings, early retirement, and layoffs.

As we are currently witnessing in the Trump administration, these tools are poorly targeted. In the case of voluntary offerings, the best employees (who consider themselves as well-suited to compete for private sector jobs) are often more likely to self-select into the programs.

Layoffs had the opposite effect: Because of the rigid statutorily-mandated procedure required to execute them, they disproportionately led to the most junior and least-tenured staff being pink-slipped.

Between 1992 and 2000, the total number of human resources staff fell by 24 percent, including a 43 percent drop in HR assistants; the number of procurement specialists dipped by 16 percent while the number of procurement support staff slid by 59 percent; the number of budget assistants dropped by 27 percent; the number of financial management/accounting jobs by 27 percent; and so on.

These cuts had a knock-on effect that was no less transformative. The share of federal workers under the age of 35 shrank from 26 percent in 1992 to under 17 percent in 2000, while the share over the age of 50 jumped from 25 percent to over 36 percent.

Due to the primarily administrative and white-collar nature of government work, the federal workforce had long been somewhat older and grayer than the broader national workforce. However, these reforms supercharged this trend, taking the federal government even further out of sync with the rest of the labor market. By 2000, in many sectors of the government, there were simply no junior people learning the ropes.

Taken together with the departure of people who had enticing private-sector options, this meant that the government walked both its best talent and its future leaders out the door together, all at once, to hit a target.

Government didn’t actually shrink; it just got harder to see and manage

In retrospect, by focusing on what they could control – namely, headcount reductions – the Clinton team succeeded in making good on the president’s headline promise, but at the expense of long-term state capacity. They succeeded in convincing the public that government’s size was the core issue, yet failed to meaningfully reduce the scope of the government’s responsibilities. In doing so, they constrained the management options available to future administrations. In fact, as the country entered the 21st century, the Clinton-era mantra of “do more with less” became “do the same with more, but hide the headcount.”

With agencies under intense political pressure to keep official headcounts steady, over time they turned to contractors to fill in the gaps. This led to an explosion in the “blended workforce” – which included contractors, grantees, and other forms of non-public employees directly supporting agency missions. By 2005, this total workforce had more people than it did in 1994 when accounting for contractors and grantees, according to analysis by a team at Brookings. Outlays to contractors shot up, especially at civilian agencies, smashing records every year. By 2023, there were nearly 2.1 contractors for every federal employee. Over time, various analyses have generally found that these contractors are more expensive than their federal counterparts. In other words the government is likely paying a premium for the dubious benefit of running a hidden workforce.

To make things worse, Reinventing Government had decimated the contracting workforce, meaning that fewer personnel had to manage more and increasingly complex contracts. The size of the procurement workforce didn’t rebound in nominal terms until 2009 and, when accounting for the real growth in contracting outlays, has never really recovered. In 1992, the government spent $13.8 million (in 2024 dollars) on contractors for every procurement professional. In 2024, that number was nearly $17 million. At the same time, the federal procurement agents’ mechanical workload grew significantly: the average contracting specialist processed 622 discrete contract actions in 1992; by 2024, that number had grown to 2,718. Some of this can be attributed to higher productivity, but it’s also the case that contracts are more complex now than they were 30 years ago.

This mismatch is implicated in some of the most visible failures in federal program delivery over the past few decades – think Healthcare.gov in 2013 or FAFSA in 2023. But they also manifest daily in less-publicized ways, creating persistent challenges for federal managers across the government.

This is not to suggest that contractors are inherently problematic. On the contrary, when deployed wisely, they can bring valuable expertise and efficiency. But doing so requires skilled, experienced federal management – a capability that weakened significantly after the Clinton-era cuts. Like any muscle, this one atrophied when it wasn’t used.

Government’s HR is still broken

Not everything can be outsourced. And when the government does hire directly, the lingering effects of Reinventing Government are still deeply felt. For one, despite staging a funeral for the 10,000 page Federal Personnel Manual in 1993 in the lobby of the Office of Personnel Management and firing a quarter of the HR professionals in the federal government, the Clinton team did little to change its fundamental hiring process.

There were some attempts at reform. The administration experimented with workforce innovations, including converting the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the Federal Aviation Commission, and Federal Student Aid into “performance-based organizations” that had exemptions from many civil service rules. It also launched personnel demonstration projects like AcqDemo at the Defense Department.

While these initiatives showed some promise, broader reform has remained out of reach. Many of these pilots have simply lingered in “trial” status for more than two decades. Meanwhile, a meaningful update to the foundational framework – the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act, which still governs most of the federal civil service – has stalled due to Congress’s persistent lack of interest in comprehensive reform.

Meanwhile, the damage Reinventing Government inflicted on the federal government’s talent pipeline has never been reversed. The top-line headcount returned to “normal” in the late 2000s as the War on Terror and the expansion of the security state elongated the executive branch’s to-do list, but the number of early-career federal employees never fully rebounded. In 1992, the median pay grade for federal workers on the General Schedule – the main pay table for the majority of federal workers since the 1940s – was GS-09, which roughly corresponds to the entry level for those with master’s degrees or a bachelor’s degree holder with two to three years of experience. By 2000, the median job was a GS-11, which roughly corresponds to the entry level for a doctoral degree holder. In 2024, the median federal employee was a GS-12, which typically requires years of specialized experience on top of a bachelor’s and graduate degree. For someone just starting out in their career, there simply aren’t many jobs in government anymore.

This problem isn’t unique to government, but it is uniquely rigid in government given the legally-mandated qualification standards from the 1940s and 1950s. Recent efforts to address these challenges via skills-based hiring have shown some promise, but will not radically change the shape of the federal workforce to something more sustainable without rethinking the underlying classification system entirely.

This means that while other large employers are re-embracing modern versions of the apprenticeship model, training their workforce from novice to expert and into management, the federal government has increasingly closed itself off to early-career talent. Instead, the government continued to fill in only the middle and senior levels of the career ladder, relegating those more junior jobs to contractors, in an effort to manage to the informal ceiling of 2.3 million federal employees that has persisted for decades.

We need to stop digging

The DOGE project, for all its Silicon Valley branding and promises of revolutionary efficiency, has essentially recreated Bill Clinton’s 1990s playbook.

As in the Clinton administration, the 2025 reductions were accomplished primarily by incentivizing both the most experienced employees to retire and the most marketable employees to find private-sector jobs. Similarly, because this round of reductions happened with minimal congressional input and virtually no action to reduce the scope of agency duties, agencies are likely to be left scrambling again to figure out how to do more and more with fewer people. While detailed demographic data about the scope of these changes will not be available for several more months, there’s no reason to think that this bloodletting won’t have the same impact as the last: driving the government’s youngest and brightest out of public service. Inertia may carry the current workforce through the remainder of this term, but the executive branch is, once again, cutting off its pipeline of future leaders — the very people we’ll need to navigate the crises of 2035 and 2045.

Meanwhile, Congress has also largely abdicated its responsibility for managing the executive branch’s to-do list. For all the discussion about reducing the scope of government, Congress passed just one single rescissions package of about $9 billion for foreign aid and public broadcasting, representing less than 0.2 percent of the federal budget. Meanwhile, total federal spending for 2025 has consistently outpaced 2024 as DOGE’s focus on deficits gives way to the practical reality of federal budget economics. The highest-profile cuts (e.g., the dismantling of USAID) have had relatively immaterial impacts on the federal government’s scope of work, and agencies will now, once again, be called on to figure out how to complete their missions without adequate personnel.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s approach may create even graver challenges for the government than Clinton’s did. While the Clinton administration may have held a skeptical view of the federal workforce, it still made an effort to treat public servants with a measure of dignity and respect. Instead, the current approach centers on creating a hostile work environment – one that demoralizes civil servants and drives them out of public service altogether. Careers in government are deliberately being made unattractive to the people we need most: public-spirited, high-achieving, middle-class professionals who want to make a difference. Aspiring public servants must now assume they will always be just one election away from an arbitrary firing, and they will be unsurprisingly hesitant to stake their family’s financial future on such uncertainty. Only the independently wealthy or those with no better prospects will choose to serve, and we will all suffer for it.

The White House and Congress now need to reckon with the ways we’ve diminished both the current administration’s own capacity and the capacity of future presidents to accomplish their congressionally authorized duties. Some agencies, like the IRS, are already looking for ways to unwind the “voluntary” reductions they encouraged just a few months ago. Meanwhile, the administration is asking agencies to prepare strategic workforce plans that presume the ability to hire in targeted areas. But it remains to be seen whether qualified applicants will raise their hands, given the contempt the Trump administration has rained down on public servants. Absent a change in strategy, it seems likely this administration is about to learn the same lesson that the Biden team discovered too late: Hiring is hard. That was true even before this year, and it will be much harder now.

It took years for the architects of Reinventing Government to come to terms with the mistakes they made, but it doesn’t have to be that way this time. Rather than shifting blame or dodging accountability, the administration and their colleagues in Congress need to realize that they’ve fallen into the Clinton trap, get serious about breaking free, and chart a new course.

The best time to fix a mistake is before you make it; the second-best time is today.

Gabe Menchaca is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center and, among many other things, is a former management staffer at the Office of Management and Budget and former management consultant. At Niskanen, he writes about civil service reform, the state capacity crisis, and other government management issues.