Free information eroded the parties. It doesn’t have to topple them.

Anyone who reflects on the history of democracies must be struck by the inverse relationship between the internal democracy of political parties and their ability to sustain democratic governance. Paradoxically, political parties that have been most internally undemocratic have proved to be the guardians of democracy. Only hierarchical organizations have proved able to perform the parties’ crucial mediating role.

A major reason why we are in such dire straits today is that America’s parties have become democratic in structure and procedure but organizationally weak. The only thing that is strong about the parties today is their label—and the fierce attachment of at least two-thirds of the voters to them. But even this is questionable, as many voters may not really like their own party but simply hate the other one. As a result, the parties are not performing their mediating role well.

All of this is reasonably known. However, we have yet to take full stock of the dramatic reduction in the cost of information—and its implications for political parties and democracy.

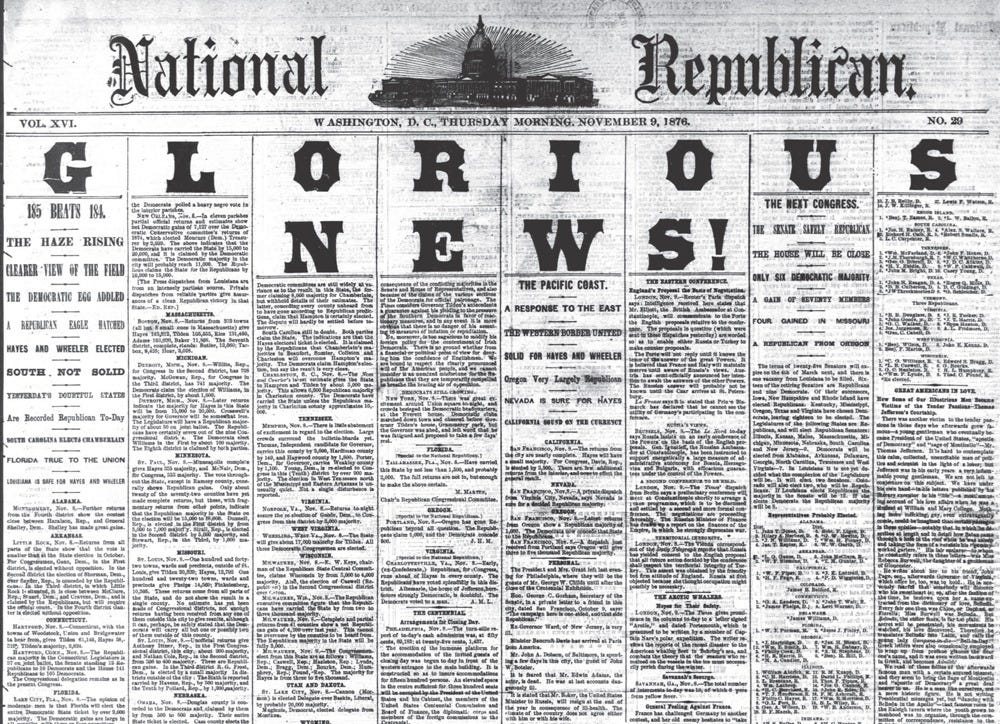

In the past, political information was expensive and hard to acquire. Control of it was one of the things that made parties stronger organizations. In the 19th century, America’s political parties even owned and operated many of the nation’s newspapers—called the “party press.” These served as mouthpieces for party messaging, as news portrayed their party in a favorable light.

Control over information meant that candidates for office needed the party to communicate—they could not simply make direct appeals to the masses. That gave the party organization a way to discipline and control candidates as well as their ideology, image, and brand. Today, the situation is nearly the reverse.

Modern telecommunications allow candidates to appeal directly to the mass public. They don’t need the party. But this has made it easier for fleeting factions and demagogic candidates to make big impressions.

Read the whole series: Partisans without parties.

Consider the fact that Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016 by raising half ($600 million) of what Hillary Clinton did ($1.2 billion). Trump forewent typical campaigning, instead deploying his talent to making provocative statements to attract “free” media attention.

Meanwhile, a cadre of media-savvy Democrats, led by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have made an outsize impact on their party despite their low standing organizationally. At no other time in American history, has a junior member of the House of Representatives commanded so much attention.

Three problems stem from the vast reduction in the cost of political information. First, it has served to abet polarization, as candidates attract more media coverage the further they are from the political center. The result is to further inflame public opinion, such that party identifiers in the electorate now hold inaccurate views of members of the other party. Partisans think their rivals are much more radical than they really are.

Second, this coverage dynamic has weakened the credibility of the national news media itself. By focusing on more highly charged statements and candidates, the media comes to appear biased to a large swath of voters. People then seek political information from social media, which is even less reliable.

Third, the political parties have become riper targets for takeover by short-lived factions, which weakens their ability to organize coalitions for policy action. This is most obvious on the Republican side with MAGA. The Democrats have held off Bernie Sanders and the progressive “squad.” But if one looks back at2020, it seems that the party only did so narrowly. Kamala Harris herself ran well to the left of her prior record, and Biden emerged victorious thanks largely to James Clyburn’s support in South Carolina.

It is clear that the strong, hierarchical parties of America’s past cannot be revived. The way forward is to seek to craft more durable factions within the parties.

Taking stock of the challenge of low information costs, it is clear that the strong, hierarchical parties of America’s past cannot be revived. The way forward is to seek to craft more durable factions within the parties. By better channeling competition within the parties, we can perhaps mitigate some of the negative polarization between them.

One way to pursue this goal might be to introduce ranked-choice voting in primary elections. This might require candidates to build more durable factions within their parties.

Another might be to adopt Brookings scholar Elaine Kamarck’s idea of “peer review” — giving current and former officeholders a larger role in presidential candidate selection. This would create more opportunities for coalition building and strengthen ties between the parties’ past, present, and future.

Whatever reforms are ultimately tried, the ability to control and channel political information in ways that assist rather than stymie parties’ role as mediating institutions should be top of mind. Only then can American government satisfactorily balance the several conflicting ends that it must serve.

Daniel DiSalvo is a professor of political science at the City College of New York-CUNY and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.