Democrats’ Wile E. Coyote Problem

For two decades, Democrats thought they could outrun the broken operating systems of government through managerial excellence. It didn’t work before, and it won’t work now.

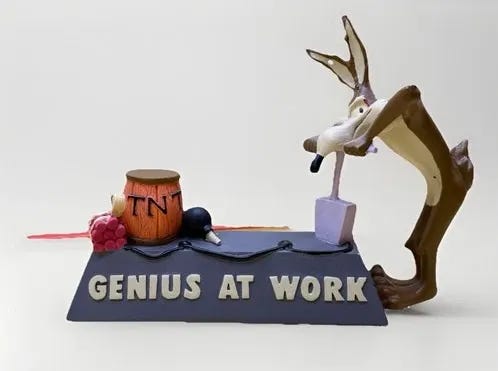

It’s the gag Americans of several generations grew up with: Wile E. Coyote hanging in midair, having chased his interminable enemy, the Road Runner, so fast that he doesn’t realize he’s run off a cliff. We watch him hang there as he realizes his predicament, and then plummets to his painful fate.

Since their debut in 1949, the pair have been locked in an endless battle waged with ACME Corporation anvils, pianos, explosives, and lots of falls. If there’s a moral kids are supposed to learn from these cartoons, it is perhaps that gravity always wins, eventually: Even a cartoon can’t outrun the laws of physics. No matter how hard Wile E. Coyote tries, he always seems to rubber-band back down to earth.

Over the last 20 years, Democrats have kept finding themselves in a similar predicament. They pass a major piece of legislation, and when the time comes to implement it in the real world, they wind up disappointed. Time and time again, they have found themselves out beyond the edge of the cliff, running really fast until they look down and physics kicks in: on Healthcare.gov, on the post-financial crisis stimulus, on the FAFSA student-aid form, on the Inflation Reduction Act, on the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, etc., they keep plummeting into the Looney Tunes canyon. At some point, Democrats have to ask themselves why this keeps happening and what can be done about it.

If Wile E. Coyote cartoons are really about the laws of physics, then these unfortunate episodes are about the laws of management. These laws – not immutable, but rather set by Congress and codified in the U.S. Code – determine how the government can hire people, buy things, budget for IT investments, etc. And, like the laws of physics, they define what’s possible for the government to achieve (or not). Much of the recent policy discourse about the Biden administration, for example, is really about these laws. For all their success in passing really large policy bills, the Biden team could not translate them into lasting wins because the rules on the books prevented the government from moving fast enough to matter.

But, unlike the immutable laws of physics, Americans can change the laws of management by pushing Congress to pass a bill, asking the president to sign it, and implementing it zealously. So why don’t they try? Why did neither the Obama nor the Biden administrations even ask Congress to make their lives easier when they were trying to implement the CHIPS Act or the Affordable Care Act?

Because, as the Democratic Party has increasingly been defined by managerialism, Democrats have convinced themselves that they are able to outsmart the systems they operate in, or “hack the bureaucracy.” That they – unlike their myopic neocon predecessors or vulgar Trumpist opponents – were capable of managing the place so well that changing the laws was a luxury rather than a necessity. That if they just deployed their considerable human capital advantage to address hard problems – like bringing in civically-minded digital experts and sprinkling them across the government – they didn’t need to bother with the slow, frustrating, uncertain, unsatisfying political process of changing laws about how the government does its business. That if Democrats just implement really hard they can hit escape velocity to defeat the laws of gravity.

Democrats need to start approaching governing with a level of humility about what management alone can accomplish. This means acknowledging an uncomfortable truth: no matter how smart, dedicated, and well-intentioned Democratic appointees are, they cannot consistently overcome the laws of physics through superior execution alone. They have to change the rules of the game by actually wielding political power and changing the law.

The disappearance of Democratic reformism

For much of American history, managing the executive branch was a joint effort between Congress and the President. When government systems broke down or proved inadequate, the response wasn’t just to try harder, it was to troubleshoot the system.

Take, for instance, the federal government’s personnel system, which is the result of a long-running debate dating to the very first Congress. For the first 150 years of the republic, Congress and the president tinkered with a variety of systems to balance political, pay equity, practical, and market concerns. In 1789, Congress rigidly defined the salaries of each role. In 1795, legislators started granting Cabinet secretaries flexibility. In 1818, they took that flexibility back before ultimately re-granting it in 1830. In 1853, they created the first government-wide salary system, and in 1923, they began differentiating by type of work. Along the way, both the executive and the legislative branches wrote a dizzying number of reports with various diagnoses, recommendations, and arguments about what the government ought to do: in 1836, 1838, 1842, 1871, 1887, 1902, 1907, and 1931, to name just a few. The familiar 15-grade General Schedule and accompanying rules have only been with us since 1949, when Harry Truman (a Democrat) signed them into law.

The tinkering habit continued well into the 20th century. When the personnel system started to show its post-war inadequacy, especially at senior levels, both Kennedy and Johnson (and, in fact, Eisenhower and Nixon, too) spent time trying to come up with proposals for a new system that would work for the type of executive management that many senior civil servants were now charged with. In late 1978, Jimmy Carter finally persuaded Congress to actually act on these proposals by making civil service reform a centerpiece of his domestic agenda, declaring to Congress in the 1978 State of the Union that “even the best organized Government will only be as effective as the people who carry out its policies. For this reason, I consider civil service reform to be absolutely vital.” This effort created the Senior Executive Service and the modern Office of Personnel Management and totally transformed the process for employee removal.

Where previous Democratic presidents saw institutional reform as essential to their policy success, recent administrations have treated it as either an afterthought or an impossibility.

Carter had good reason to believe in the power of government reform, having come fresh off a similar effort in Georgia, where he dramatically reorganized and reformed the bureaucracy as governor from 1971-1975. In his second State of the State speech in 1972, he foreshadowed his 1978 State of the Union when he argued that large-scale government reform could enable reform to Georgia’s schools, prisons, colleges, tax code, etc.: “The truth is that we cannot solve these long existing problems either effectively or within our present tax laws without a well organized Executive Department.”

Bill Clinton, several years later, cut a very similar profile as the last Democrat to seriously prioritize this kind of structural reform. Like Carter, his immediate prior experience had been as a governor; in Arkansas, he had spent 11 years effectively leading one of the poorest states in the country. When he got to Washington, he set about attempting to “reinvent” the federal government and to make it “work better and cost less” through systematic changes to federal operations. While the effort had mixed results and some unintended consequences that weakened long-term state capacity, Clinton at least recognized that institutional change was required and tried working with Congress to that end.

But something shifted after Clinton. Barack Obama came to office fresh out of the Senate and with perhaps the most talented technocratic policy team in modern Democratic history. Yet, unlike his predecessors, he made virtually no effort to work with Congress on government reform, preferring to stress executive action. Despite facing implementation challenges on everything from the stimulus to healthcare, the Obama administration’s instinct was always to manage harder and create ever-more czarships, but not to change the underlying constraints. The same pattern repeated under Joe Biden: a former senator, surrounded by smart people, pushed through well-designed policies, yet paired those efforts with (at best) deprioritization and (at worst) disinterest in the structural reforms that would make implementation of those policies easier.

Some will argue that this is due not to disinterest but congressional dysfunction that would make changes to the law impossible. Surely, some of this is Congress’ (and self-admittedly Mitch McConnell’s) fault. But as former legislators, both Obama and Biden were able to tame congressional coalitional politics enough to pass large, complicated, and high-impact laws like the ACA or the infrastructure law by making them a central part of their agendas. However, neither president seemed to see reform as the necessary precondition of effective government that it turned out to be. To be sure, both administrations continued the tradition of releasing President’s Management Agendas that started under the George W. Bush Administration, but those focused primarily on marginal management strategies rather than structural reform. In 2010, the Obama team did pass a bill on management reform. But the Government Performance and Results Act Modernization Act’s title was revealing: It primarily updated the complicated, familiar-to-consultants system of performance measurement and goal-setting procedures established under the Bush administration rather than making material changes to how agencies did their work.

The Obama-Biden years thus represent a fundamental break with Democratic tradition. Where previous Democratic presidents saw institutional reform as essential to their policy success, recent administrations have treated it as either an afterthought or an impossibility, as something that could or needed to be handled through superior execution rather than legislative change.

The rise of liberal managerialism

This shift didn’t happen in a vacuum. Educational polarization is now perhaps one of the most well-documented and argued-over trends in politics. According to Pew, in 1994, Republicans had a 10-point advantage among registered voters with a college degree and by 2023, that group had flipped to favor the Democrats by 13 points.

This shift changed how the Democratic Party approached its work. As Jia Lynn Yang recently argued in the New York Times:

Soon the need for moral integrity and technical mastery to run a complex government became not just a mode for governing but also ends in themselves. Beginning in the 1970s, a new generation of Democratic leaders arrived to tout these values to voters, more so than their Republican rivals. Experience in gnarly hand-to-hand political combat was fading out. Expertise, ideally honed at an elite university, was in.

However, while most of the ink spilled on this shift has been about its impact on Democratic electoral outcomes, comparatively little has been said about its impact on the party’s approach to governing outcomes.

The technocrats that increasingly serve as the primary labor pool for Democratic political operations (i.e., highly-educated lawyers, management consultants, and non-profit professionals) have specific worldviews honed by their training and prior experience. In particular, they exhibit what Megan Stevenson succinctly describes as the engineer’s view, which “presumes [that the world adheres to] a mechanistic structure that can be predictably manipulated to achieve social goals.” In this view, deft operation of the levers of power is all that is required to bring about social change, rather than large-scale overhauls of systems. One sees it reflected in the public policy master’s programs that produce many of these people: core curricula are dominated by statistics and microeconomics classes to support elegant policy design. Legislators, too, are attracted to this type of thinking because it follows that incrementally better legislative language will allow them to deliver on their promises.

It’s no surprise, then, that the party dominated by technocrats embraced Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler’s work on “nudges” in 2008, with President Obama eventually appointing Sunstein as head of the powerful Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which oversees regulations and form design for the federal government under the promise to bring a keen behavioral scientist’s approach to governing. Similarly, in 2014, after the catastrophic implosion of Healthcare.gov, this same impulse led the White House to create the U.S. Digital Service under the assumption that rotating deployments of highly-capable management professionals (this time, technologists) would also address these problems – something of a “nudge” for the bureaucracy to guard against future blow-ups.

The Biden team took this approach and put its own spin on it. In their political and staffing strategy, they attempted to make progress on as many discrete, individually-highly-polling priorities as possible to deliver for various parts of the coalition. This ‘deliverism,’ plausible in the manager’s mechanical worldview, rested on a “presumption of a linear and direct relationship between economic policy and people’s political allegiances.” This approach created awkward tradeoffs – for example, the tension between both wanting to usher in a new era of clean infrastructure investment while also rigidly enforcing domestic sourcing requirements – and left management to clean up the mess on its own. Rather than acknowledging that there are tradeoffs in governing, the president insisted that superior execution could overcome them, arguing that “[t]hey’re all important ... We oughta be able to walk and chew gum at the same time.” But actually, it turns out that walking and chewing gum at the same time is really, really hard and sometimes you faceplant. This, in turn, sank the entire agenda at the ballot box both because it meant many agencies failed to implement their big goals and because voters didn’t connect with this status-report approach to government of “ticking down the issues as opposed to having a theory.”

Twenty years into this turn, it is time to start thinking more critically about whether re-running the same play will work again after Democrats failed to outrun gravity again and again. Both USDS’ founders and behavioral economists eventually came to find that the problems they were addressing in the 2010s were more fundamental than managerial. Democrats would do well to learn from their reflections.

The closing of the conservative mind

Democrats are mulling their failures at the same time as they watch a president ignore countless rules to impose his will. While the mainstream of the party still believes that core liberal norms are both a moral imperative and a differentiating advantage with the public, some voices are calling on Democrats to similarly test the limits next time they take power – to mimic the MAGA and tech-right model and “just do things.” Constitutional and philosophical concerns aside, this strategy would be unlikely to succeed as a matter of governance; early indications are that it isn’t working well for the Trump administration, either.

Increasingly, the MAGA right has decided it prefers illiberal domination to the hard work of institutional reform. When they have dipped their toes into reforming the operating model of government, they’ve chosen largely to waste their time on performative culture-war gestures like banning paper straws or implementing partisan loyalty tests. And as the GOP has moved away from traditional conservative policy expertise toward populist performance, many of the wonks and policy professionals who might have provided alternatives to Democratic approaches have either left politics entirely or switched sides. This exodus accelerated during the Trump era, when certain factions discovered they could gain more from attacking expertise itself than from demonstrating mastery of complex issues.

The “brain drain” from the Republican Party is well-attested to and increasingly obvious to outside observers, and in some ways, it has made conservatives as path-dependent as Democrats. In a recent interview with Ross Douthat, anti-DEI crusader Chris Rufo admitted that conservatives’ human capital problem had gotten so bad that they “cannot fully staff the Department of Education” and therefore had to dismantle it to accomplish any of their policy goals. This incapacity – the Department of Education is by far the smallest cabinet-level agency with only about 4,200 total staff – has led the MAGA movement to eschew the pursuit of structural changes to make government work better in favor of turning the “move fast and break things” Silicon Valley mantra into a governing strategy, aiming to bypass legal and democratic constraints entirely rather than reform them.

To be sure, the MAGA movement can combine the conservative preference for domination with bureaucratic efficacy on its top priorities. This combination is most visible in figures like Russ Vought, the OMB director mythologized for his bureaucratic acumen. But normative concerns aside, even Vought’s signature issue concedes a fundamental limit of the “just do things” strategy: His exotic ideas about impoundment merely expand the president’s ability to decline to do things. The conservative strategy is inherently destructive—it can tear down existing systems but struggles to build anything lasting in their place. Even the signature project for which the administration did get congressional approval, the construction of a $170 billion deportation machine, is off to a shaky start, given the trouble the administration has run into with the courts and public opinion.

Rather than following Republicans through the looking glass, Democrats should embrace the only alternative: working with Congress to actually change the system.

You can just do (effective) things (with Congress)

For all the retrospectives on the Biden administration that focus on the negatives, there was (in fact) a huge policy bill that avoided falling into the cartoon canyon.

When legislators crafted the Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act of 2022 to provide healthcare and benefits to veterans exposed to burn pits and other toxins, they recognized that the Department of Veterans Affairs would need fundamentally different capabilities to handle a massive influx of new claims and provide expanded healthcare services. So, they gave the VA new authorities: streamlining hiring procedures for medical professionals, investing in IT and HR staff to handle the crush of onboarding, expanding contracting flexibility for healthcare services, and simplifying the benefit determination processes for toxic exposure claims. This came also on the heels of Congress moving in 2011 to a two-year advanced appropriations cycle for large portions of VA activities, freeing the agency from the tyranny of constant shutdowns caused by Congress’ own inability to legislate. In other words, they made the structural reforms necessary to enable effective implementation.

The results speak for themselves. While other major federal initiatives have struggled with implementation, the PACT Act has been rolling out with remarkable success. Between September 2022 and the end of 2024, VA hired over 45,000 new staff on net, growing its workforce by about 10 percent in just two years. While no major implementation is free from challenges, in general veterans are getting care, claims are being processed, and the system is scaling up to meet demand. This didn’t happen just because the VA suddenly got better at managing within existing constraints (although the dizzying speed with which the quality of management at VA has improved over the last decade under both Republican and Democratic leadership is notable); it happened because Congress changed the constraints.

This is just an example of what is possible when policymakers think systemically about implementation challenges rather than just hoping that good intentions and hard work will overcome structural obstacles. It shows that the choice isn’t between ambitious policy goals and practical implementation, but rather that it’s between doing the political work of institutional reform and accepting repeated failure. In VA’s case, it was particularly fortunate to have had an uncommonly-seasoned leader in Denis McDonough who had personally learned hard lessons about implementation failure with Healthcare.gov and deftly anticipated issues with enough time to influence the bill this time around.

But one successful example doesn’t mean that Washington has cracked the code. Part of the reason that the PACT Act worked was because it had a discrete, well-defined problem where the implementation challenges were obvious, leadership was exceptionally experienced, and the bipartisan constituency demanding results was powerful. Most Democratic policy priorities don’t have these advantages. Climate action, healthcare reform, infrastructure investment—these require sustained implementation across multiple agencies over many years, exactly the kind of complex execution that the current system handles poorly. There are too many forces that act on any one program for management to outrun them all.

The bill is coming due

Consider this highly plausible scenario: It’s 2028, and there’s a new Democratic candidate shaping an agenda. Political strategists are mapping out the first 100 days, and someone raises the question of government reform legislation. “Well,” comes the inevitable response, “the candidate has lots of other priorities, and voters don’t really care about federal operations. They want action on healthcare, climate, and the economy. Can we manage for a couple years without burning political capital on bureaucratic reform?”

The answer has to be no. If they neglect government reform again, Democrats will fail and it will be their fault. This kind of thinking is exactly what has trapped Democrats in the Wile E. Coyote pattern. Every Democratic administration tells itself it can manage around broken systems long enough to achieve its policy goals, and every Democratic administration discovers too late that the systems shape the outcomes more than the managers do – that “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

If your after-action report on BIL implementation or IRA deployment doesn’t include recommendations for structural, government-wide changes to federal hiring, procurement, or budgeting systems that go beyond executive action, you’re missing the real lesson. Any serious, forward-looking policy agenda must insist on government reform as an unavoidable and non-negotiable first step, including:

Reforming the civil service so that it is simpler to administer, faster to deploy, and more competitive in the labor market. The entire system is an outgrowth of an industrial-age approach to management and needs to be replaced wholesale, not just tinkered with at the edges;

Reducing administrative procedure that binds government more excessively than industry and puts publicly-sponsored enterprise at a structural disadvantage. Helping people is hard enough without having to comply with increasingly onerous rules on things like public comment and procurement that add lots of time and little value;

Taking back control from contractors and vendors, that is, investing in internal capacity first before turning to a services and technology industrial base that is too often incentivized to keep the government broken. The government doesn’t need to do everything itself, but it needs to close the sophistication gap with industry to ensure it can actually manage vendors; and

Fixing the broken appropriations process that denies both Congress and presidents the ability to make deliberate choices, instead favoring arbitrary adjustments to continuing resolutions. Complicated budget scoring and procedural arcana haven’t stopped yawning deficits, but they have made the process so cumbersome and unintuitive that agencies and Congress have given up.

If this seems hard, that’s because it is. But, the good news is that it’s been done before. Throughout American history there are windows that open and allow for transformative legislative session progress. The last two were in the postwar 1940s and throughout the 1970s, a decade of remarkable productivity both before and after Watergate. Americans are still living today in the world built by Congress in those years. However, just as companies build up “technical debt” by putting off upgrades to their systems for years, the government has built up significant “policy debt” by refusing to make these updates to its operating model while the system decayed.

Now the bill is coming due.

Fixing things, though, requires engaging with the political process that Democrats have increasingly tried to avoid. Congressional politics are indeed awful. They’re slow, frustrating, often irrational, and almost always unsatisfying. But they’re also the only way to change the underlying rules that govern how the federal government operates. You can’t avoid Congress forever and Democrats who think they can are deluding themselves. While it’s true that conservative legal theorists and the Supreme Court continue to grant new powers to the President, Democrats must understand that these are asymmetric tools not fit for their purposes: they can break but they cannot build. Prioritizing government reform may be politically or personally painful for committed partisans, but it’s the only way to prevent greater pain later.

If Democrats don’t internalize and act on this lesson now, the next Democratic president, whoever and whenever that is, will find themselves in the exact same situation as their predecessors and as Wile E. Coyote: running fast in midair off the side of the cliff, feeling like they’re making progress right up until they look down and realize they’re in free fall.

Wile E. Coyote never learns his lesson, but that doesn’t mean Democrats can’t now. The cartoon physics of American politics may be absurd, but unlike actual physics, Congress has the power to change them. The question is whether anyone has the guts to try.

Gabe Menchaca is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center and, among many other things, is a former management staffer at the Office of Management and Budget and former management consultant. At Niskanen, he writes about civil service reform, the state capacity crisis, and other government management issues.