Abundance dreams of center-left wonks are being realized in red states

The movement would do well to build bridges to Republican areas where growth defuses zero-sum fights.

At the heart of pro-abundance politics is a fundamental disconnect: While the intellectual muscle behind it largely comes from the center-left, the building and growth it seeks to spur is most likely to take place in red states, with critical support from Republican officeholders.

This disconnect became apparent in the two-tiered recovery from the pandemic. After the initial stay-at-home orders, red and blue states veered in different directions. Republican states such as Florida, Texas, and South Dakota were quick to reopen, while large blue states took a more cautious approach. The red states won out economically, with California, New York, and Illinois bleeding population at faster rates to the Sun Belt and lower-tax states.

The pandemic also shone a spotlight on frayed supply chains and the service-heavy parts of the economy, like healthcare and education, that are afflicted by “cost disease socialism.” Noting the political sclerosis in blue states that hobbled new housing or infrastructure investment, center-left wonks took a newfound interest in bringing supply-side growth to their own backyard.

As they advance reforms, the new supply siders would do well to borrow from the old-school supply siders, with the focus they placed on economic growth as a magic elixir that enabled them to square policy circles, like the idea that cutting tax rates could increase revenue. This is a lesson that’s being applied in high-growth red states, with more physical room for growth and fewer regulatory barriers to building.

Sun Belt powerhouses have been adding population at a rapid clip, all while reinventing their local economies. Underlying growth has undercut NIMBY opposition.

Take housing, the policy area that abundance advocates concern themselves with most. Markets in California and New York face hard geographical and practical constraints — the ocean on one side, and mountains or maximum commuting distances on the other. Scarcity benefits existing homeowners, and they form a powerful voting bloc resistant to change. Building in the largest coastal metros means reorganizing existing housing stock, whether through upzoning or building taller. That requires cutting through a thicket of vested interests that simply don’t exist in places with laxer zoning and plentiful space for new development.

Geographic constraints are not the only roadblock to abundance in blue states. A bigger one is creeping economic stagnation. Considered a decade ago the mecca of innovation, San Francisco is now seen as a troubled city where only the ultra-rich can afford to live — side by side with uncontrolled homelessness. Chicago bleeds residents from high taxes and slackened post-pandemic law enforcement. While New York has emerged from the pandemic relatively unscathed, it has seen an exodus of financial firms to states like Florida. The freedom of white-collar workers to do their jobs from anywhere is yielding an advantage to red states with lower taxes and living costs.

And diminished growth creates a vicious cycle that makes housing reform even harder. The lower the growth in a state or metro, the more likely it is that new housing will result in declining property values, sparking a fierce backlash from existing owners. To solve this problem, reformers would do best to address the underlying causes of out-migration: high taxes and urban blight in the form of crime and homelessness.

Abundance advocates are confronting a deep status quo bias in the electorate that one party alone is unlikely to fix. Many of the central tenets of the movement have weak support across the partisan divide.

On the other extreme lie Texas and Florida, with zero income taxes and, actually, high-quality public services. These Sun Belt powerhouses have been adding population at a rapid clip, all while reinventing their local economies. Miami has been reborn as a second Silicon Valley, with a skyline transforming faster than anywhere this side of Dubai. (And much the same could be said of downtown Austin.) Dallas and Houston, with laxer zoning restrictions and freedom to grow on all sides, have long been destinations for newcomers from north, east, and west. Of course, the sprawling growth in these places is not always the kind preferred by urbanists, and each will have to deal with its own challenges, like the crisis in the Florida homeowners’ insurance market. But underlying growth has undercut NIMBY opposition, since existing homeowners have less fear of their ox being gored by new development.

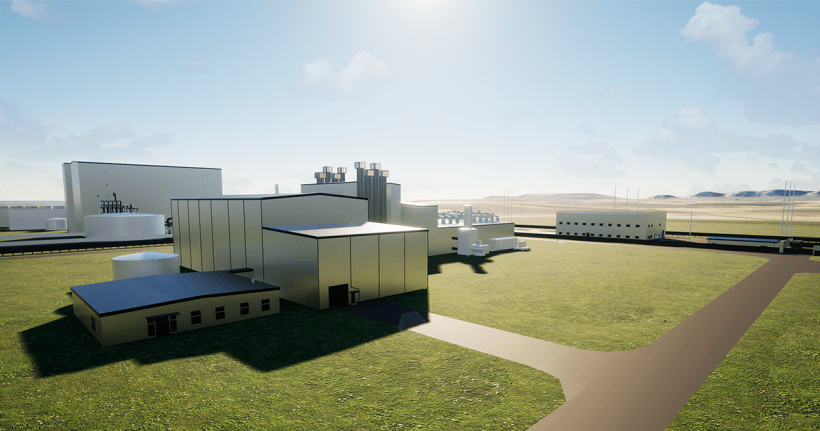

On energy and climate, the story is much the same. A swing state at the national level but Republican at the state level, Georgia has become a hub for solar and electric-vehicle battery production. Wyoming has just broken ground on a next-generation nuclear plant backed by Bill Gates — with the support of the state’s Republicans. Meanwhile, midnight blue California was recently debating taking its last nuclear plant offline, a move it ultimately rejected.

An abundance movement may never take hold at the federal level — but it might not need to. Most of the building will happen at the state and local levels, so that’s where its focus should be. State and local Republicans are quite happy to seize on new economic development opportunities, whether on housing or clean energy. Others have observed the paradox that the majority of the “green” investments in the Inflation Reduction Act are happening in red states and counties. Subsidies aside, there are good reasons for this: The best places to build out wind and solar capacity are in rural areas largely in the South, Midwest, and the West — mostly Republican territory. These projects face their own NIMBY challenges, but are less controversial among elected officials and don’t face the same buzzsaw of opposition one must go through to build in big metro areas.

Building political infrastructure exclusively on one side of the partisan divide will only polarize these issues along tribal lines.

How are voters responding to all this? An Echelon Insights poll on abundance-related issues conducted in May 2023 did show more Democratic voter support for policies advocated by neoliberal Substackers and X users. But this pattern of support is not consistent across every issue, and many of the central tenets of the movement have weak support across the partisan divide. On housing, the YIMBY view is relatively unpopular, losing 57 to 36 percent when the choice is between building more housing by reducing regulatory and zoning requirements versus giving existing homeowners more of a say so that property values don’t go down. Here, Democrats are more supportive of the “growth” position, though just barely, 47 to 45 percent — while Republicans break 26 to 69 percent against.

But on nuclear energy, this pattern is reversed: Republicans support nuclear power as a safe and reliable source of clean energy by 51 to 40 percent, while Democrats oppose building new nuclear power plants due to safety concerns by a margin of 56 to 36 percent.

Many have noted that the environmental review process has been weaponized against building out clean energy infrastructure, suggesting a strange-bedfellows coalition between free-market conservatives and climate activists to fix it. But changes to environmental review are broadly unpopular across the electorate: Just 31 percent of voters agree that “we need to relax the current environmental review process that makes it too hard to build projects that would reduce carbon emissions,” versus 60 percent who say that we need to keep existing processes to “preserve the natural beauty of the environment” and “protect the rights of property owners.” These levels were virtually identical in both parties.

Abundance advocates are confronting a deep status quo bias in the electorate that one party alone is unlikely to fix. Building political infrastructure exclusively on one side of the partisan divide will only polarize these issues along tribal lines, making any reform harder to achieve and less resilient in the face of the inevitable changes in party control.

Robust private-sector growth can grease the wheels of reform. Growth is what makes it possible to build new housing without angering current homeowners. Clean energy deployment as economic development for rural areas is a winner across the partisan spectrum. And Republican governors have political as well as policy reasons to show that their states are growing and successful, as opposed to the dysfunction of states like California.

Finding champions among growth-minded Republican officeholders could be the key to the movement’s success.

There might come a day when new growth from more liberal locales such as Austin or Atlanta will undermine Republican control in red states, altering the political dynamics, but this largely doesn’t seem to have happened so far. Florida has shifted right, Texas Republicans are getting an assist from border Hispanics in keeping the state red, and current polling in Arizona and Georgia suggest that Joe Biden’s victories there in 2020 may have been one-offs. And if the Sun Belt does become more of a political battleground, there’s every reason to think that Democrats as they win office will continue these policies, using Colorado Gov. Jared Polis as a model.

With an abundance agenda more likely to take root at the state level, and especially in red and purple states, finding champions among growth-minded Republican officeholders could be the key to the movement’s success.

Patrick Ruffini is a founding partner of Echelon Insights, a leading polling and data firm, and the author of Party of the People: Inside the Multiracial Populist Coalition Remaking the GOP.

Image: U.S. Department of Energy